Stateless Pipeline with Async Stream

Jan 6, 2024

You can check out the code here.

After the series on pools and pipeline (Part I, Part II) was published, a friend graciously pointed me to another approach that would be simpler for a lot of occasions with less boilerplate code. It uses the async Stream trait and its iterator-like adaptors in StreamExt. That Stack Overflow post was from 2018, but up till today (Jan 2024), the Stream trait is still not stablized into the Rust standard library. However, what worked back then still works today. It is so useful, and has become my go-to option in many cases. So let’s look at it together.

There are some good guides on streams1 2 3. Note that both the futures and Tokio crates have their own StreamExt utility traits and methods. As of today, futures’ implementation has a broader selection. We will be using some of them here.

At first, I was having a little hard time wrapping my head around streams. A Stream is the async-equivalent to an Iterator. Iterators are lazy, and they will get executed at the end of the method chain by methods like collect() and for_each(). Streams are lazier, compounded by the fact that Rust futures are lazy. This introduces another degree of freedom and complexity into the richness of Rust functional programming that iterators champion. Because of this, we are able to express concurrency and parallelism directly in the stream method chaining. In the sync land, you’d need Rayon to achieve parallelism (we’ll compare them a bit later).

Comment: Little did I know when writing this post, that the relationship between iterators and futures in Rust has a long history4, both of which are fundamentally driven by what defines the modern Rust programming language with a need for zero-cost abstraction. In addition, there exhibits some elegant symmetry between them5 6 (Maxwell’s Equations everyone?) These referenced articles were posted very recently (fresh off the Boats, sorry, can’t help it) and they are very relevant and insightful. So I would recommend a read if you are inclined to dig deeper.

Stateless Pipelines

Let’s look at the example in that post. I altered it a bit for clarity.

use anyhow::Result

use futures::{stream, StreamExt};

use reqwest::Client;

const N_TASKS: usize = 8;

const CONCURRENT_REQUESTS: usize = 4;

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() -> Result<()> {

let client = Client::new();

let urls = vec!["https://api.ipify.org"; N_TASKS];

stream::iter(urls)

.enumerate()

.map(|(idx, url)| {

let client = &client;

async move {

let t = std::time::Instant::now();

println!("{idx}: Fetching {}...", url);

let resp = client.get(url).send().await?;

let bytes = resp.bytes().await?;

println!("{idx}: Took {:.2}ms", t.elapsed().as_millis());

anyhow::Ok((idx, bytes))

}

})

.buffered(CONCURRENT_REQUESTS)

// .buffer_unordered(CONCURRENT_REQUESTS)

.for_each(|res| async {

match res {

Ok((idx, b)) => println!("{idx}: Got {} bytes", b.len()),

Err(e) => eprintln!("Got an error: {}", e),

}

})

.await;

Ok(())

}

We define a vector urls of 8 entries. With some iterator-like syntax, we map() and for_each() to get it started. Because we are doing async here, we need to .await at the end. It all makes sense. But what are we returning in map() and for_each(), and what is buffered()/buffer_unordered()?? Let’s withhold the burning curiosity and run this example:

0: Fetching https://api.ipify.org...

1: Fetching https://api.ipify.org...

2: Fetching https://api.ipify.org...

3: Fetching https://api.ipify.org...

0: Took 398ms

0: Got 13 bytes

4: Fetching https://api.ipify.org...

1: Took 424ms

1: Got 13 bytes

3: Took 424ms

5: Fetching https://api.ipify.org...

2: Took 424ms

2: Got 13 bytes

3: Got 13 bytes

6: Fetching https://api.ipify.org...

7: Fetching https://api.ipify.org...

4: Took 89ms

4: Got 13 bytes

6: Took 110ms

5: Took 110ms

5: Got 13 bytes

6: Got 13 bytes

7: Took 110ms

7: Got 13 bytes

Four tasks in a batch are indeed running concurrently, followed by another batch! So let’s draw a comparison with the actor model here. Is there an actor defined? No. Is there a resource? Sort of - the reqwest::Client. When we use the client, we only need an immutable reference (or a cheap clone with tokio::spawn()). This is unlike a database connection or an ML model. We are using the client as a stateless bundle of code, and passing it around to tasks to download from links. It is in fact a fairly typical use case, and this approach with async streams is perfect for it. Additionally, in the Stack Overflow post, it was also shown how to use tokio::spawn() to get multi-threaded/multi-core parallelism.

Type Reasoning

So let’s get back to the previous question about map(), for_each(), and buffered()/buffer_unordered(). Let’s compare Iterator with Stream:

pub trait Iterator { type Item; // Provided methods fn map<B, F>(self, f: F) -> Map<Self, F> where Self: Sized, F: FnMut(Self::Item) -> B { ... } fn for_each<F>(self, f: F) where Self: Sized, F: FnMut(Self::Item) { ... } } pub trait StreamExt: Stream { // Provided methods fn map<T, F>(self, f: F) -> Map<Self, F> where F: FnMut(Self::Item) -> T, Self: Sized { ... } fn for_each<Fut, F>(self, f: F) -> ForEach<Self, Fut, F> where F: FnMut(Self::Item) -> Fut, Fut: Future<Output = ()>, Self: Sized { ... } fn buffered(self, n: usize) -> Buffered<Self> where Self::Item: Future, Self: Sized { ... } fn buffer_unordered(self, n: usize) -> BufferUnordered<Self> where Self::Item: Future, Self: Sized { ... } }

It is curious. The map() signatures are quite similar, but it’s quite different for for_each(). For Iterator, it’s a straightforward closure that doesn’t return anything. For Stream, there is a trait bound F: FnMut(Self::Item) -> Fut, which means the closure needs to return a future (which is bound by Fut: Future<Output = ()>, a future that doesn’t return anything)!

If we dig a little deeper into async Rust, we will see that this is what an async function/closure does. In the RFC:

An

async fn foo(args..) -> Tis a function of the typefn(args..) -> impl Future<Output = T>. The return type is an anonymous type generated by the compiler.

So Stream’s for_each() needs an async closure, which is a closure that returns a future. That’s really what the type system tells us. Let’s look at what we gave to for_each():

.for_each(|res| async {

match res {

Ok((idx, b)) => println!("{idx}: Got {} bytes", b.len()),

Err(e) => eprintln!("Got an error: {}", e),

}

})

You see that async? That’s exactly it.

This is a good opportunity to share some notes of my Rust learning journey. Coming from a less typed background, it surely was an uphill battle to reason with Rust types in such intensity, and adding async to it was truly icing (salt) on the cake (wound)! On one hand, as a Rust programmer, you kind of have to understand this to get through the beginner’s phase, and this is where a lot of people give up. On the other hand, after these concepts begin to take shape in your head, Rust starts to become magical, and (many of) you might get really addicted - well, until you reach a certain point as a library developer, with some thorny fights with the compiler (here is a rebuttal).

What about map()?

Wait, so… Why are the two map()’s signatures so similar? You could certainly pass a regular closure to Stream’s map(). In fact, the doc uses it as an example:

Note that this function consumes the stream passed into it and returns a wrapped version of it, similar to the existing map methods in the standard library.

use futures::stream::{self, StreamExt}; let stream = stream::iter(1..=3); let stream = stream.map(|x| x + 3); assert_eq!(vec![4, 5, 6], stream.collect::<Vec<_>>().await);

If we used map() this way, there wouldn’t be any async magic happening. What is important yet left implied, is that you can pass it a closure that returns a future. After all, the trait bound F: FnMut(Self::Item) -> T does not impose what the closure is supposed to return (just a generic T). So it can certainly be a future!

This is in fact how exactly we enabled async concurrency from the stream in our example. Look:

.map(|(idx, url)| {

let client = &client;

async move {

let t = std::time::Instant::now();

println!("{idx}: Fetching {}...", url);

let resp = client.get(url).send().await?;

let bytes = resp.bytes().await?;

println!("{idx}: Took {:.2}ms", t.elapsed().as_millis());

anyhow::Ok((idx, bytes))

}

})

The closure we gave to map() returns an async move {}. What is this? It’s an async block, a.k.a. a future! You could have written something like with for_each(), or below to use the async closure syntax, because, an async closure is a closure that returns a future:

// won't compile, due to the need to move `client` vs the `FnMut` bound in `F: FnMut(Self::Item) -> T`

.map(|(idx, url)| async move {

let t = std::time::Instant::now();

println!("{idx}: Fetching {}...", url);

let resp = client.get(url).send().await?;

let bytes = resp.bytes().await?;

println!("{idx}: Took {:.2}ms", t.elapsed().as_millis());

anyhow::Ok((idx, bytes))

})

// or

// still won't compile, due to capturing of `idx` and `url` by reference

.map(|(idx, url)| async {

let t = std::time::Instant::now();

println!("{idx}: Fetching {}...", url);

let resp = client.get(url).send().await?;

let bytes = resp.bytes().await?;

println!("{idx}: Took {:.2}ms", t.elapsed().as_millis());

anyhow::Ok((idx, bytes))

})

Those two exact blocks won’t actually compile, unfortunately. Because the future escapes the closure where it’s defined when the closure returns, you have to prove to the compiler the future captures the right things and owns the right things. If you feel a bit overwhelmed (I did many times), just recall that async Rust loves to annotate futures with a move when spawning tasks, like async move {}. When in doubt, try using the explicit regular closure returning an async block approach, and take clones/immutable references right before the async move {} line. Move things around and let the compiler teach you where you are.

Comment: Again, little did I know when writing this post, I stumbled upon one of the items Rust key contributors highlighted in 2023 and would like to resolve in the near future7. Reading up on them and a few of their other posts (see refs) after writing my own truly opened my eyes. I am very grateful for being enlightened from their insights, and remain hopeful these features are stablized for broad adoption.

What about buffered()/buffer_unordered()?

Look at the signatures:

fn buffered(self, n: usize) -> Buffered<Self> where Self::Item: Future, Self: Sized { ... } fn buffer_unordered(self, n: usize) -> BufferUnordered<Self> where Self::Item: Future, Self: Sized { ... }

The Self::Item is just Stream::Item. It is saying, these two methods want to be chained to a stream that produces futures. Well, guess what we have after map()? A stream of futures! This is where async execution is enabled for the futures it consumes from up the chain, bound by CONCURRENT_REQUESTS at a time. By specifying buffered(CONCURRENT_REQUESTS), the results are received in the input futures’ order, and by buffer_unordered(CONCURRENT_REQUESTS), they are received in the order they are completed, potentially less wait from arriving at the input futures’ ordering.

Stacking up

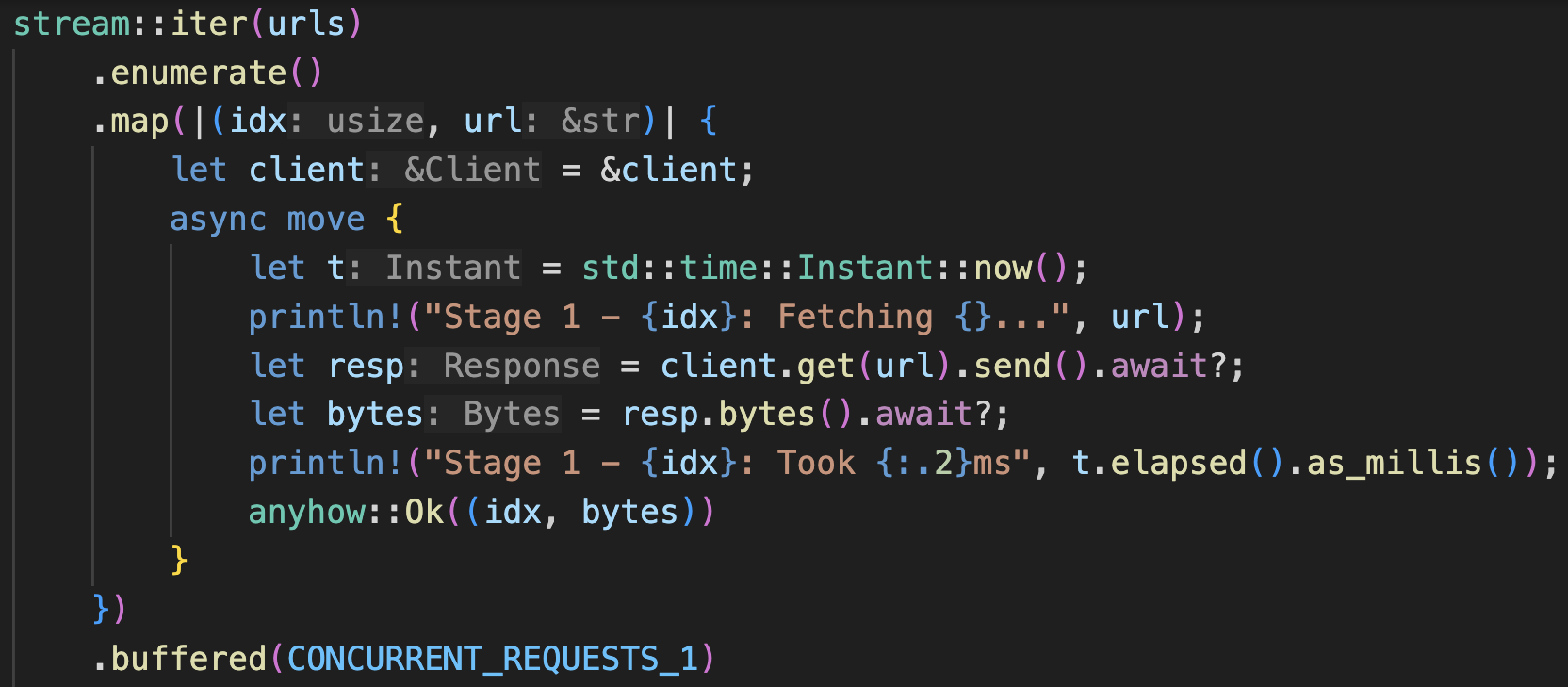

We can create multiple stages of the pipeline by adding more map() and buffered()/buffer_unordered(). Why would we do that? After all, our pipeline is stateless, so we don’t have many resources to manage, so why do we still need different stages? Well, consider a pipeline that downloads from a source, and uploads to a destination. Even if the common “resource” is just a stateless client, the source and destination servers might exhibit different capacities and rate limiting rules. Using the same number of workers might not be compatible with both - one might be under the rate limit, the other might blow over. Our pipeline will then exhibit a modal behavior, swinging from all workers working on one stage, to all workers working on another at a time. In a way, the resources are external, and we need to capture that. By having separate stages, we can configure different numbers of workers to match the external capacities. Different stages will then work continuously to overlap with other stages. Let’s write it out:

const N_TASKS: usize = 8;

const CONCURRENT_REQUESTS_1: usize = 4;

const CONCURRENT_REQUESTS_2: usize = 4;

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() -> Result<()> {

let client = Client::new();

let urls = vec!["https://api.ipify.org"; N_TASKS];

stream::iter(urls)

.enumerate()

.map(|(idx, url)| {

let client = &client;

async move {

let t = std::time::Instant::now();

println!("Stage 1 - {idx}: Fetching {}...", url);

let resp = client.get(url).send().await?;

let bytes = resp.bytes().await?;

println!("Stage 1 - {idx}: Took {:.2}ms", t.elapsed().as_millis());

anyhow::Ok((idx, bytes))

}

})

.buffered(CONCURRENT_REQUESTS_1)

.map(|res| async move {

match res {

Ok((idx, b)) => {

let t = std::time::Instant::now();

println!("Stage 2 - {idx}: Starting...");

let s = String::from_utf8(b.to_vec())?;

tokio::time::sleep(std::time::Duration::from_millis(500)).await;

println!("Stage 2 - {idx}: Took {:.2}ms", t.elapsed().as_millis());

anyhow::Ok((idx, s))

}

Err(e) => Err(e),

}

})

.buffered(CONCURRENT_REQUESTS_2)

.for_each(|res| async {

match res {

Ok((idx, s)) => println!("Finally: {idx}: Got string with length {}", s.len()),

Err(e) => eprintln!("Finally: Got an error: {}", e),

}

})

.await;

Ok(())

}

Here is the output. You can see the stages are overlapping - task 0 went to “Finally” early on.

Stage 1 - 0: Fetching https://api.ipify.org...

Stage 1 - 1: Fetching https://api.ipify.org...

Stage 1 - 2: Fetching https://api.ipify.org...

Stage 1 - 3: Fetching https://api.ipify.org...

Stage 1 - 2: Took 425ms

Stage 1 - 0: Took 435ms

Stage 1 - 1: Took 434ms

Stage 1 - 4: Fetching https://api.ipify.org...

Stage 1 - 3: Took 434ms

Stage 2 - 0: Starting...

Stage 2 - 1: Starting...

Stage 2 - 2: Starting...

Stage 2 - 3: Starting...

Stage 2 - 0: Took 502ms

Finally: 0: Got string with length 13

Stage 1 - 5: Fetching https://api.ipify.org...

Stage 1 - 6: Fetching https://api.ipify.org...

Stage 1 - 4: Took 502ms

Stage 2 - 1: Took 502ms

Finally: 1: Got string with length 13

Stage 1 - 7: Fetching https://api.ipify.org...

Stage 2 - 2: Took 502ms

Finally: 2: Got string with length 13

Stage 2 - 3: Took 502ms

Finally: 3: Got string with length 13

Stage 2 - 4: Starting...

Stage 1 - 7: Took 102ms

Stage 1 - 5: Took 102ms

Stage 1 - 6: Took 102ms

Stage 2 - 5: Starting...

Stage 2 - 6: Starting...

Stage 2 - 7: Starting...

Stage 2 - 4: Took 502ms

Finally: 4: Got string with length 13

Stage 2 - 5: Took 502ms

Finally: 5: Got string with length 13

Stage 2 - 6: Took 502ms

Finally: 6: Got string with length 13

Stage 2 - 7: Took 502ms

Finally: 7: Got string with length 13

Extension: Add a Writer Output

There are many ways to extend our pipeline to do more things. Let’s look at the typical input and output - files. We will also think about concurrency and parallelism from the start.

The input could be many files, and concurrency/parallelism can go from there. In that case, put file names into the initial vector, and create a stream by Stream::iter(filenames). Each file will be a unit of work. Alternatively, if you have one large file, you could use the stream! macro from the async-stream crate to define an iterator from file lines.

It’s worth going into the output a bit more. The output writer is usually required to be mut, and it might be tricky to set up in the async context. First, we need a writer, and we modify the for_each closure to use the writer:

use tokio::fs::File;

use tokio::io::{BufWriter, AsyncWriteExt};

// ...

let mut writer = BufWriter::new(File::create("output.txt").await?);

// ...

.for_each(|res| {

async {

match res {

Ok((idx, s)) => {

println!("Finally: {idx}: Got string with length {}", s.len());

writer.write_all(format!("{}\n", s).as_bytes()).await.unwrap();

},

Err(e) => eprintln!("Finally: Got an error: {}", e),

}

}

})

.await;

// ...

writer.flush().await?;

The compiler is mad:

error: captured variable cannot escape `FnMut` closure body

--> src/bin/streamext.rs:46:13

|

13 | let mut writer = BufWriter::new(File::create("output.txt").await?);

| ---------- variable defined here

...

45 | .for_each(|res| {

| - inferred to be a `FnMut` closure

46 | / async {

47 | | match res {

48 | | Ok((idx, s)) => {

49 | | println!("Finally: {idx}: Got string with length {}", s.len());

50 | | writer.write_all(format!("{}\n", s).as_bytes()).await.unwrap();

| | ------ variable captured here

... |

53 | | }

54 | | }

| |_____________^ returns an `async` block that contains a reference to a captured variable, which then escapes the closure body

|

= note: `FnMut` closures only have access to their captured variables while they are executing...

= note: ...therefore, they cannot allow references to captured variables to escape

The message is quite helpful. However, there is one thing left out - if this were a reader, we could take out an immutable reference, and the lifetime rules would be met. The real problem is we need a mutable reference to the writer here. And the fact that async enables concurrency, we are potentially taking out multiple mutable references! And importantly, there is no multi-threading going on here - no spawn(), no executing on other threads, but just plain concurrency. This is not to say multiple for_each() calls are actually executing concurrently, but just that the state machine mechanism in async Rust requires the future to outlive the for_each() closure, thus carrying all captured references with it, immutable or mutable. We just need a proof that we know what we are doing in a safe way. Does it remind you of anything? Yes, internal mutability and Rc<RefCell<T>>! This was one of my first few mental blocks learning Rust. Initially, I could not understand why no more than one mutable references could exist at the same time. If you are like me, think about it in this case and it might further your understanding. The compiler is here to help you with even plain concurrency, to ensure concurrent tasks will not modify something you are not expecting to change!

The following question is, what is changing here? Why do we need a mutable reference to the writer? Well, it’s writing something, and it manages some buffer, or some system file descriptor. The way to get out of it is again, Rc<RefCell<T>>:

use std::cell::RefCell;

use std::rc::Rc;

// ...

let writer = Rc::new(RefCell::new(BufWriter::new(File::create("output.txt").await?)));

// ...

.for_each(|res| async {

match res {

Ok((idx, s)) => {

println!("Finally: {idx}: Got string with length {}", s.len());

writer

.borrow_mut()

.write_all(format!("{}\n", s).as_bytes())

.await

.unwrap();

}

Err(e) => eprintln!("Finally: Got an error: {}", e),

}

})

.await;

// ..

writer.borrow_mut().flush().await?;

This works! Check out the output.txt! What a journey.

Currently, async Rust does not handle file IO very efficiently (absent io-uring). In fact, the tokio::fs is mostly a wrapper to std::fs with a dedicated big thread pool for blocking IO tasks8 9. As a result, there is a lot of overhead moving tasks to the thread pool and results back if IO tasks are small. If your output file IO is slowing you down, consider using async-channel, or Flume to send() tasks in the async land, and receive_blocking() in the sync land with spawn_blocking(). It’s a very useful pattern.

Comparison with Rayon in Sync Land

It’s worthwhile drawing some comparison between async streams to Rayon parallel iterators in the sync land. These are two different beasts. Rayon is designed to achieve multi-threaded/multi-core parallelism for high-compute-density tasks that fully take up CPU cycles. It expects you to feed it tasks that won’t wait on IO for too long, and usually no more than N of (physical or logical with hyperthreading) cores number of tasks are running in parallel. Async Rust solves the complementary problem, where your tasks have heavy IO needs, and you need to spawn many more tasks to take up even one CPU’s cycles (this is concurrency) to saturate computing resources - we are assuming IO limit is high. In Rust, async tasks can also be truly multi-threaded/multi-core parallel, depending on the executor, like Tokio. The downside is you need to ensure IO function calls are not blocking, but yielding, which creates a “paralel universe” to the sync land. This has been a point of frustration to async Rust, and yet is tied to everything that makes modern Rust the way it is - zero-cost abstraction. You are encouraged to read up4 on it.

From a user’s perspective, however, the tasks are always a mix of both CPU- and IO- intensive. If you really want it, you could run CPU-intensive tasks with async, and IO-intensive tasks with Rayon. Performance may degrade quite a lot, but it should still work.

With Rayon, there are two approaches to achieve parallelism. You stick a .par_iter()/.into_par_iter() to a collection with a known length (not an iterator), like a Vec, or a HasMap, and Rayon uses divide-and-conquer to cut up the sequence. The advantage of this approach is work division is done on the stack with recursion, and is extremely fast when work scheduling is the bottleneck otherwise. The disadvantage is you can’t convert any iterator with unknown length to a parallel one this way. To do that, Rayon added par_bridge(). However, one notable behavior difference is the collected results from it is not ordered according to the original iterator. You could borrow the logic from here as a remedy.

With async streams, you can express concurrency with or without parallelism, and define stages with an arbitrary number of tasks executed at the same time. There is more flexibility, due to the nature of async, and of course, more complexity.

More on Async

Async Rust is a very interesting topic. If interest follows, please check out a few articles10 11 12 4 7 5 6 I found insightful.

-

https://tokio.rs/tokio/tutorial/streams ↩

-

https://www.qovery.com/blog/a-guided-tour-of-streams-in-rust/ ↩

-

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/70599317/is-there-any-point-in-async-file-io ↩

-

https://darkcoding.net/software/linux-what-can-you-epoll/ ↩

-

https://ryhl.io/blog/async-what-is-blocking/ ↩

-

https://www.infoq.com/presentations/rust-2019/ ↩

-

https://users.rust-lang.org/t/green-threads-vs-async/42159/2 ↩