Pools and Pipeline with Tokio (Part I - RPC)

27 Dec 2023 Comments

You can check out the code here.

I am working on a Rust project that goes through a lot of small tasks in parallel. These tasks are primarily IO intensive, like downloading objects from S3, processing them, and storing the results somewhere else. Since this is a fairly representative use case in data engineering, I am keen on working out a generalized design pattern that can be customized to more scenarios. This post lays out such a pattern, and I will explain some of the specific considerations and choices made along the way.

In a distributed setting, there would be a global task queue to feed the inputs from a head node, a first-stage worker pool pulling tasks off the queue, and working through them in parallel. Then those workers would feed the outputs into another node-local queue, which connects to a second-stage worker pool to do some other parallel processing. The stages propagate, and each stage’s worker pool holds some special resources. When started and stabilized, the worker pools would run together and overlap the task execution between stages, benefiting from “pipeline parallelism”.

In the past, I would reach for Python to carry out this type of data pipelining. Due to its slowness and global interpreter lock (GIL), I had to jump through hoops to obtain multi-core usage to get decent throughput, and the resulting design was still riddled with thread contention, high memory usage, and unnecessary (de-)serialization if multiprocessing is used. If you are serious enough, you would probably want to use a distributed framework, like Dask, or Ray. They are all very useful, but I would like to make a case for single-node setups with a fast language - it’s flexible in iterative development and deployment, and it’s really efficient. Often, you don’t need a cluster, but just a node and some code to get similar throughput, especially when there are constraints at the source or the final destination.

The official release of the Rust AWS SDK was a final push for me. Since it’s using Tokio as its async runtime, and Tokio blends concurrency and multi-threaded parallelism together, it’s an ideal substrate for this work. Tokio also has smooth escape hatches in and out of the async world, so you know you are covered with the edge cases. In this post, we use the words “concurrent” and “parallel” in a similar vein, versus “sequential” / “serial”. However, There is an important but different angle to distinguish concurrency and parallelism regarding CPU cores, threads, and task scheduling.

On a high level, given a source of tasks, what do we need to process them in parallel? Of course, we need worker pools to have workers that run in parallel. But that’s not enough. Depending on the worker pool API, we might need a bridge from the serial land to the parallel land. If the worker pool adopts the message streaming model with separate send() and recv(), behaving like a processing queue, this bridge is implied and provided. However, if the worker pool adopts the client-server RPC model, there need to be multiple task submitters hitting the “server” to get the workers working in parallel.

The RPC Model

Let’s zoom in on the RPC model, building off the example provided by the excellent post Actors with Tokio. In that post, an actor design was proposed, with the ability to complete the full request-response cycle of a client call to the actor. Let’s write this out as the starting point. First, the actor itself (modified to add a 500-millisecond sleep in the message handler):

use tokio::sync::{mpsc, oneshot};

enum ActorMessage {

GetUniqueId { respond_to: oneshot::Sender<u32> },

}

struct MyActor {

receiver: mpsc::Receiver<ActorMessage>,

next_id: u32,

}

impl MyActor {

fn new(receiver: mpsc::Receiver<ActorMessage>) -> Self {

MyActor {

receiver,

next_id: 0,

}

}

async fn handle_message(&mut self, msg: ActorMessage) {

match msg {

ActorMessage::GetUniqueId { respond_to } => {

self.next_id += 1;

tokio::time::sleep(tokio::time::Duration::from_millis(500)).await;

// The `let _ =` ignores any errors when sending.

//

// This can happen if the `select!` macro is used

// to cancel waiting for the response.

let _ = respond_to.send(self.next_id);

}

}

}

async fn run(&mut self) {

while let Some(msg) = self.receiver.recv().await {

self.handle_message(msg).await;

}

}

}

Note we store next_id to demonstrate the actor holding a mutable state that changes upon client requests. This is just one reason why you would use the actor model. In practice, you could choose it because you want to hold an immutable resource that is expensive to create and destroy, like a database connection, or an ML model.

Then the actor handle, with which we reference the actor:

#[derive(Clone)]

pub struct MyActorHandle {

sender: mpsc::Sender<ActorMessage>,

}

impl MyActorHandle {

pub fn new() -> Self {

let (sender, receiver) = mpsc::channel(8);

tokio::spawn(async move { MyActor::new(receiver).run().await });

Self { sender }

}

pub async fn get_unique_id(&self) -> u32 {

let (send, recv) = oneshot::channel();

let msg = ActorMessage::GetUniqueId { respond_to: send };

// Ignore send errors. If this send fails, so does the

// recv.await below. There's no reason to check the

// failure twice.

let _ = self.sender.send(msg).await;

recv.await.expect("Actor task has been killed")

}

}

Note that in practice, you could have MyActor().handle_message() send a Result type with a custom Err variant, and MyActorHandle().get_unique_id() can return that to the caller to handle errors. We’ll do that in Part II.

We would create and refer to the actor with:

let actor = MyActorHandle::new();

Actor Pool

This is just one actor. How can we make a pool of them? We need to consider the ergonomics from the caller’s perspective. We would like to have one single instance to call, instead of having to go through some selection logic. So these actors in the pool should share the same request channel. Tokio’s mpsc channel does not allow multiple actors to share the receiver. So we either need to wrap it with a Arc<Mutex<mpsc::Reciver>>, or use an mpmc channel, such as from async-channel, or Flume. With that, we convert the MyActorHandle into a MyActorPool:

// adapt MyActor to using async_channel

struct MyActor {

receiver: async_channel::Receiver<ActorMessage>,

next_id: u32,

}

// ...

#[derive(Clone)]

pub struct MyActorPool {

sender: async_channel::Sender<ActorMessage>,

}

impl MyActorPool {

pub fn new(num_actors: usize) -> Self {

let (sender, receiver) = async_channel::bounded(8);

for _ in 0..num_actors {

let receiver = receiver.clone();

tokio::spawn(async move { MyActor::new(receiver).run().await });

}

Self { sender }

}

pub async fn get_unique_id(&self) -> u32 {

let (send, recv) = oneshot::channel();

let msg = ActorMessage::GetUniqueId { respond_to: send };

// Ignore send errors. If this send fails, so does the

// recv.await below. There's no reason to check the

// failure twice.

let _ = self.sender.send(msg).await;

recv.await.expect("Actor task has been killed")

}

}

Now let’s create 4 actors in a pool and call it 8 times:

use pools_and_pipeline::my_actor_pool::MyActorPool;

const N_TASKS: u64 = 8;

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() {

let pool = MyActorPool::new(4);

let mut res_all = vec![];

for i in 0..N_TASKS {

let t = tokio::time::Instant::now();

println!("{i} starting...");

let res = pool.get_unique_id().await;

res_all.push(res);

println!("{i} ended in {}ms", t.elapsed().as_millis());

}

println!("res_all = {:?}", res_all);

}

Your output might be different, because different actor workers are taking the calls, incrementing & returning their internal counters.

0 starting...

0 ended in 502ms

1 starting...

1 ended in 501ms

2 starting...

2 ended in 502ms

3 starting...

3 ended in 502ms

4 starting...

4 ended in 502ms

5 starting...

5 ended in 501ms

6 starting...

6 ended in 502ms

7 starting...

7 ended in 502ms

res_all = [1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2]

More Callers

The pool is not processing tasks concurrently or in parallel at the moment. Each call has to wait for the response in the RPC model. This is when the “bridge” is needed. Obviously, we need to parallelize the callers:

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() {

let pool = MyActorPool::new(4);

let mut join_set = tokio::task::JoinSet::new();

let mut res_all = vec![];

for i in 0..N_TASKS {

let pool = pool.clone();

join_set.spawn(async move {

let t = tokio::time::Instant::now();

println!("{i} starting...");

let res = pool.get_unique_id().await;

println!("{i} ended in {}ms", t.elapsed().as_millis());

res

});

}

while let Some(res) = join_set.join_next().await {

res_all.push(res.unwrap());

}

println!("res_all = {:?}", res_all);

}

This spawns 8 callers in a JoinSet, so that we could harvest the results. This time, the first 4 calls get executed concurrently/in parallel. So do the last 4 calls, but they have to wait until the pool has more capacity.

0 starting...

3 starting...

2 starting...

5 starting...

6 starting...

4 starting...

7 starting...

1 starting...

5 ended in 502ms

3 ended in 502ms

2 ended in 502ms

0 ended in 502ms

1 ended in 1004ms

4 ended in 1004ms

6 ended in 1004ms

7 ended in 1004ms

res_all = [1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2]

Big Practical Concerns

There are two main issues with this simplified caller code.

- The source task list could be very long. Spawning caller tasks without bounds and letting them wait on the RPC is bad. Async tasks are cheap, but we don’t want the design to not have a bound. It’s also much harder to exit gracefully this way.

- The

JoinSetwill actually hoard the memory of every task it spawns but not consumed. We need to consume from it concurrently/in parallel.

The first one can be resolved by a semaphore. The second one requires a bigger change - we need to spawn a separate task to process the results. As it turns out, we can’t use JoinSet for this, and mpsc channels are the ideal pattern. The task submitter holds the Sender part of the channel, and the task receiver holds the Receiver part. The receiver will break out of its loop when all Senders are dropped by the individual submitted tasks. It is up to you to either put the submitter or the receiver in a background task. I prefer the former, because mentally I am more interested in the results. It also makes graceful shutdown more natural as the receiver loop ends.

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() {

// create pool

let pool = MyActorPool::new(4);

// submitter & receiver comm

let (sender, mut receiver) = tokio::sync::mpsc::channel(4);

// submit tasks

tokio::spawn(async move {

// concurrency control

let sem = std::sync::Arc::new(tokio::sync::Semaphore::new(4));

for _i in 0..N_TASKS {

let permit = sem.clone().acquire_owned().await.unwrap();

let pool = pool.clone();

let sender = sender.clone();

tokio::spawn(async move {

let _permit = permit; // own the permit

let t = tokio::time::Instant::now();

println!("{_i} starting...");

let res = pool.get_unique_id().await;

println!("{_i} ended in {}ms", t.elapsed().as_millis());

sender.send(res).await.unwrap();

});

}

});

// wait for all tasks to finish

let mut res_all = vec![];

while let Some(res) = receiver.recv().await {

res_all.push(res);

}

println!("res_all = {:?}", res_all);

}

0 starting...

1 starting...

2 starting...

3 starting...

3 ended in 502ms

0 ended in 502ms

2 ended in 502ms

1 ended in 502ms

4 starting...

5 starting...

6 starting...

7 starting...

7 ended in 502ms

6 ended in 502ms

4 ended in 502ms

5 ended in 502ms

res_all = [1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2]

If you don’t care about the results, but just would like to process through tasks where internally work is done. You could use a TaskTracker to avoid the extra complexity of spawning a separate task.

Full Program

This pattern will take you quite far in practice. You could wire different pools owning different resources, adjust pool sizes, and the main entry point could blast through millions and billions of tasks. You could intercept the SIGINT, and stop sending tasks, and wait for existing tasks to finish gracefully to resume later. You could use a progress bar crate to track progress.

This is a simple CTRL+C handler:

use std::sync::{

atomic::{AtomicBool, Ordering},

Arc,

};

pub struct InterruptIndicator {

state: Arc<AtomicBool>,

}

impl InterruptIndicator {

pub fn new() -> Self {

let state = Arc::new(AtomicBool::new(false));

let state_ = state.clone();

tokio::spawn(async move {

tokio::signal::ctrl_c()

.await

.expect("failed to install CTRL+C handler");

state_.store(true, Ordering::Relaxed);

});

Self { state }

}

pub fn is_set(&self) -> bool {

self.state.load(Ordering::Relaxed)

}

}

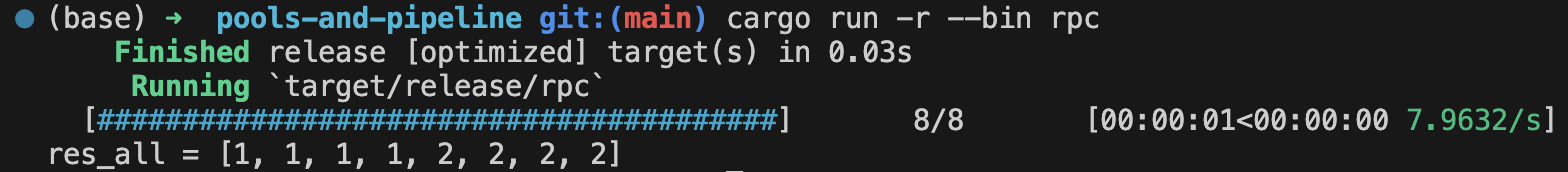

This is the full main program with a progress bar from Indicatif:

use indicatif::{ProgressBar, ProgressStyle};

use pools_and_pipeline::my_actor_pool::MyActorPool;

use pools_and_pipeline::utils::InterruptIndicator;

use std::sync::Arc;

use tokio::sync::Semaphore;

use tokio::task::JoinSet;

const N_TASKS: u64 = 8;

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() {

// attach CTRL+C handler

let interrupt_indicator = InterruptIndicator::new();

// create pool

let pool = MyActorPool::new(4);

// submitter & receiver comm

let (sender, mut receiver) = tokio::sync::mpsc::channel(4);

// submit tasks

tokio::spawn(async move {

// concurrency control

let sem = Arc::new(Semaphore::new(4));

for _i in 0..N_TASKS {

if interrupt_indicator.is_set() {

println!("Interrupted! Exiting gracefully...");

break;

}

let permit = sem.clone().acquire_owned().await.unwrap();

let pool = pool.clone();

let sender = sender.clone();

tokio::spawn(async move {

let _permit = permit; // own the permit

// let t = tokio::time::Instant::now();

// println!("{_i} starting...");

let res = pool.get_unique_id().await;

// println!("{_i} ended in {}ms", t.elapsed().as_millis());

sender.send(res).await.unwrap();

});

}

});

// wait for all tasks to finish

// make pretty progress bar

let pb = ProgressBar::new(N_TASKS);

let sty = ProgressStyle::with_template(

"{spinner:.cyan} [{bar:40.cyan/blue}] {pos:>7}/{len:7} [{elapsed_precise}<{eta_precise} {per_sec:.green}] {msg}"

).unwrap().progress_chars("#>-");

pb.set_style(sty);

let mut res_all = vec![];

while let Some(res) = receiver.recv().await {

res_all.push(res);

pb.inc(1);

}

pb.finish();

println!("res_all = {:?}", res_all);

}

^CInterrupted! Exiting gracefully...

⠚ [####################>-------------------] 4/8 [00:00:00<00:00:02 1.9913/s]

[########################################] 8/8 [00:00:01<00:00:00 7.9635/s]

res_all = [1, 1, 1, 1, 2]

You probably want to use Anyhow to handle errors and convert the unwrap() into ? propagation for good measure.

To be Continued… The Streaming Model

Earlier we discussed that, if the multi-worker pool behaves like a processing queue instead of a server, the bridge to parallelism was implied and provided. I will spec out that design in a separate post - (Part II).