A Week of PyO3 + rust-numpy (How to Speed Up Your Data Pipeline X Times)

06 Jun 2023 Comments

Updated Oct 7, 2024: use unsafe but correct and faster array content copy to go from 3x to 4x.

You can check out the code here.

If you are like me (and many others), you’d need a strong reason to learn a new programming language (my journey). It’s a big commitment, and requires a lot of days and nights to do it right. Even for languages like Python that boast simplicity, under the hood there is a lot going on. For many developers, Python is the non-negotiable gluing/orchestrating layer that sits closest to them, because it frees them from the distractions that are not part of the main business logic, and has evolved to become the central language for ML/AI.

Rust on the other hand, requires a lot from a developer up front. Beyond a “hello world” toy example, it gets complex quickly, presenting a steep learning curve. It’s an amazing modern systems language, extremely fast and portable. However, my main programming activities have been in ML and data pipelines, operating on the Python (high) level, so I haven’t seriously tried to learn it.

Python’s ML and data story mostly revolves around the Python numeric ecosystem, which really took off when NumPy brought in the array interface and advanced math to become the “open-source researchers’ MATLAB”, that eventually kicked off almost 20 years of ML/AI development. Following that script, there emerged many Python-based workflows and packages that benefited from faster compiled languages as extension modules. They could be exploratory routines in scientific computing (physics, graphics, data analytics) that needed to be flexible yet efficient. They could be deep learning frameworks. They could also be distributed pipelines that ingest & transform large amounts of data, or web servers with heavy computation demands. The interoperating layer was fulfilled by Cython, SWIG, and Boost.Python. pybind11 grew as a successor to Boost.Python (different authors!) to offer C++ integration, and got good traction in late 2010.

On the Rust side, PyO3 has been getting a lot of love. Developers love Rust’s safety guarantees, modern features, and excellent ecosystem, and have been leveraging ndarray, rust-numpy to interoperate with NumPy arrays from Python to speed up performance-critical sections of their code. This has tremendous appeal to me, and has granted me an overwhelming reason to learn Rust with the PyO3 + rust-numpy stack. Let this be my own “command line program” (from the Book) example. It wasn’t easy to get started this way… Took me through confusion, frustration, and finally, enlightenment in a short span of days. I hope this post can help you get started with your own journey.

Before pulling up the sleeves, let’s peek into Rust and PyO3’s ecosystem. PyO3 has great docs, which is much appreciated. I benefited a lot from the Articles section, reading about other developers’ journeys1 2 3. (Note: this article also joined the list!)

The GIL and NumPy

It’s worth mentioning that you can already use NumPy for most of the heavy lifting. It is a fast compiled extension module, and already has the ability to release the GIL (global interpreter lock) on many occasions. Releasing the GIL is important for compute-intensive tasks because it enables Python threads to truly utilize multiple CPU cores. It is a big deal with today’s multicore CPU architecture (goodbye Moore’s Law). For example, if you run the code below in enough loops, and check CPU usage, multiple CPUs will be engaged.

import os

# need to set OMP_NUM_THREADS=1 to avoid MKL/OpenBlas using internal multithreading to confound the measurement

# also much faster overall due to less thread contention (only python threads)

os.environ["OMP_NUM_THREADS"] = "1"

from concurrent.futures import ThreadPoolExecutor

import numpy as np

from tqdm import tqdm

def func():

for _ in range(10):

return np.dot(np.random.rand(1000, 1000), np.random.rand(1000, 1000))

if __name__ == "__main__":

N_tasks = 32

N_workers = 8

pool = ThreadPoolExecutor(max_workers=N_workers)

futures = []

for _ in range(N_tasks):

futures.append(pool.submit(func))

for future in tqdm(futures):

_ = future.result()

So why do you need additional Python extensions? Well, not all operations can release the GIL. And those can be most of the code, even code that interacts with NumPy.

My Data Pipeline Problem

This is what I ran into. I have many msgpack files generated from some ML routine that packs tens of thousands of NumPy arrays into bytes in each, like generated below.

from typing import Iterator

from concurrent.futures import ThreadPoolExecutor

import numpy as np

import msgpack

from tqdm import tqdm

from loguru import logger

SIZE_ARRAY_DIM = 512

COUNT_PER_MSGPACK_UPPERBOUND = 50000

if __name__ == "__main__":

with open("bytes_vectors.msgpack", "wb") as f:

for i in range(COUNT_PER_MSGPACK_UPPERBOUND):

vector = np.random.rand(SIZE_ARRAY_DIM).astype(np.float32)

msgpack.pack(vector.tobytes(), f)

There are a lot of them sitting somewhere. I need to use this to iterate through them in Python. It’s worth noting in this particular example one could even write this msgpack iterator in Rust, but in reality there was some custom logic that was hard to replicate. So we will stick with Python for the demo’s sake. You could gain a lot of performance by writing this in Rust, especially with many Python threads, because iterating over Python iterators is slow, and bound by the GIL.

def iterate_msgpack(filename):

with open(filename, "rb") as handle:

unpacker = msgpack.Unpacker(handle)

try:

for item in unpacker:

yield item

except Exception as e:

logger.error(e)

The main logic is to have many thread workers, each processing one msgpack file and returning a large NumPy array with the content to the main thread. The main thread will do something with the arrays from thread workers in sequence. For every iteration of a msgpack file, we copy the vector into the pre-allocated NumPy array. This copy involves individual Python objects, so is bound by the GIL.

def take_iter_py(iterator: Iterator[bytes], np_vectors: np.ndarray) -> int:

idx = 0

for bytes_vector in iterator:

try:

vector = np.frombuffer(bytes_vector, dtype=np.float32).reshape(SIZE_ARRAY_DIM)

np_vectors[idx] = vector

except ValueError:

print(f"Array size does not match!")

continue

idx += 1

return idx

def process_py(filepath):

np_vectors = np.empty((COUNT_PER_MSGPACK_UPPERBOUND, SIZE_ARRAY_DIM), dtype=np.float32)

count = take_iter_py(iterate_msgpack(filepath), np_vectors)

np_vectors = np_vectors[:count]

return np_vectors

We use the same ThreadPoolExecutor setup as earlier to get a benchmark. We use 8 thread workers to go through 32 tasks on an M1 Macbook Pro. Each task goes through one msgpack file. Here we simply reuse the same msgpack file.

if __name__ == "__main__":

filepath = "bytes_vectors.msgpack"

N_tasks = 32

N_workers = 8

pool = ThreadPoolExecutor(max_workers=N_workers)

logger.info("With Python / thread pool:")

futures = []

for _ in range(N_tasks):

futures.append(pool.submit(process_py, filepath))

for future in tqdm(futures):

_ = future.result()

Output:

With Python / thread pool:

32/32 [00:03<00:00, 8.05it/s]

Why Not Process Workers?

A common workaround in Python pipeline processing is to use multiprocessing, or the newer ProcessPoolExecutor. Instead of using threads that are bound by the GIL, one could fork/spawn multiple Python processes to enable true parallelism. Process workers have their own memory space, and only interact with the main process through (de-)serialization of objects. In our case, the input is a sequence of msgpack file paths, and output is a sequence of their NumPy arrays.

from concurrent.futures import ProcessPoolExecutor

# ...

pool = ProcessPoolExecutor(max_workers=N_workers)

logger.info("With Python / process pool:")

futures = []

for _ in range(N_tasks):

futures.append(pool.submit(process_py, filepath))

for future in tqdm(futures):

_ = future.result()

Output:

With Python / process pool:

32/32 [00:06<00:00, 4.86it/s]

It’s actually slower! Why is that? Usually this trick works quite well, a simple swap to ProcessPoolExecutor to access many CPU cores. Here, it is slower because another source of latency crept in - (de-)serialization of the big NumPy arrays! Each returned array is sized at 50000 * 512 * 4 / 1024**2 = 98MB.

To demonstrate this, let’s construct a simple test, where we don’t do anything but return a newly allocated NumPy array.

def func():

return np.empty((50000, 512), dtype=np.float32)

# ...

pool = ProcessPoolExecutor(max_workers=N_workers)

logger.info("With Python / process pool:")

futures = []

for _ in range(N_tasks):

futures.append(pool.submit(func))

for future in tqdm(futures):

_ = future.result()

Output:

With Python / process pool:

32/32 [00:05<00:00, 5.40it/s]

It’s already quite slow, let alone more operations stacked on top. Clearly, going back to thread workers avoids this unnecessary overhead. Try swapping back ThreadPoolExecutor and see it/s go up to the order of hundreds of thousands - we are not doing anything here, so of course it should be fast.

PyO3 + rust-numpy to Rescue

This is the case where compiled extensions can help. PyO3 and rust-numpy provide an excellent interface to deal with anything that might come your way. There are a lot of other great articles I referenced earlier that can get you set up using maturin. Assuming you complete the common steps, let us create a Rust extension package that implements a take_iter() function. What’s really amazing is the interoperability - it can take a Python iterator!

In src/lib.rs, where the main logic lives, we write

use numpy::ndarray::{s, ArrayViewMut1};

use numpy::PyReadwriteArray2;

use pyo3::exceptions::PyValueError;

use pyo3::prelude::*;

use pyo3::types::{PyBytes, PyIterator};

const SIZE_ARRAY_DIM: usize = 512;

const F32_SIZE: usize = 4;

fn copy_array(src_bytes_vector: &[u8], dst_vector: &mut ArrayViewMut1<f32>) -> Result<(), String> {

if src_bytes_vector.len() == dst_vector.len() * F32_SIZE {

// f32 from msgpack

// copy bytes in f32 le format to dst_vector

// safe but slower

// for (dst, src) in dst_vector.iter_mut().zip(

// src_bytes_vector

// .chunks_exact(F32_SIZE)

// .map(|x| f32::from_le_bytes(x.try_into().unwrap())),

// ) {

// *dst = src;

// }

// unsafe but correct & faster

unsafe {

std::ptr::copy_nonoverlapping(

src_bytes_vector.as_ptr() as *const f32,

dst_vector.as_mut_ptr(),

dst_vector.len(),

);

}

return Ok(());

} else {

return Err(format!(

"Array size is {}, does not match {}!",

src_bytes_vector.len(),

dst_vector.len() * F32_SIZE

));

};

}

#[pymodule]

fn rust_ext(m: &Bound<PyModule>) -> PyResult<()> {

#[pyfn(m)]

fn take_iter(

py: Python,

iter: Bound<PyIterator>,

mut np_vectors: PyReadwriteArray2<f32>,

) -> PyResult<usize> {

// First collect bytes into a Rust-native vector.

// We can't release the GIL here because we are dealing with a Python object.

let mut raw_list: Vec<Vec<u8>> = vec![];

for item in iter {

raw_list.push(item?.downcast::<PyBytes>()?.as_bytes().to_vec());

}

let mut vectors = np_vectors.as_array_mut();

// Bytes are read as f32 arrays and copied into the passed in NumPy array.

// We release the GIL here so other Python threads can run in true parallelism.

py.allow_threads(|| {

if raw_list.len() > vectors.dim().0 {

return Err(PyValueError::new_err("Too many items in iterator!"));

}

if vectors.dim().1 != SIZE_ARRAY_DIM {

return Err(PyValueError::new_err(format!(

"2D NumPy array has {} columns, does not match {}!",

vectors.dim().1,

SIZE_ARRAY_DIM

)));

}

let mut idx = 0;

for src_bytes_vector in raw_list {

let mut dst_vector = vectors.slice_mut(s![idx, ..]);

if let Err(e) = copy_array(&src_bytes_vector, &mut dst_vector) {

eprintln!("Error: {}. Skipping...", e);

continue;

}

idx += 1;

}

Ok(idx)

})

}

Ok(())

}

Run maturin develop --release to compile and install as a Python package. And in Python code, write

import rust_ext

# ...

def process_rs(filepath):

np_vectors = np.empty((COUNT_PER_MSGPACK_UPPERBOUND, SIZE_ARRAY_DIM), dtype=np.float32)

count = rust_ext.take_iter(iterate_msgpack(filepath), np_vectors)

np_vectors = np_vectors[:count]

return np_vectors

# ...

pool = ThreadPoolExecutor(max_workers=N_workers)

logger.info("With Rust extension / thread pool:")

futures = []

for _ in range(N_tasks):

futures.append(pool.submit(process_rs, filepath))

for future in tqdm(futures):

_ = future.result()

Output:

With Rust extension / thread pool:

32/32 [00:00<00:00, 33.58it/s]

That’s 4x faster than the Python code!

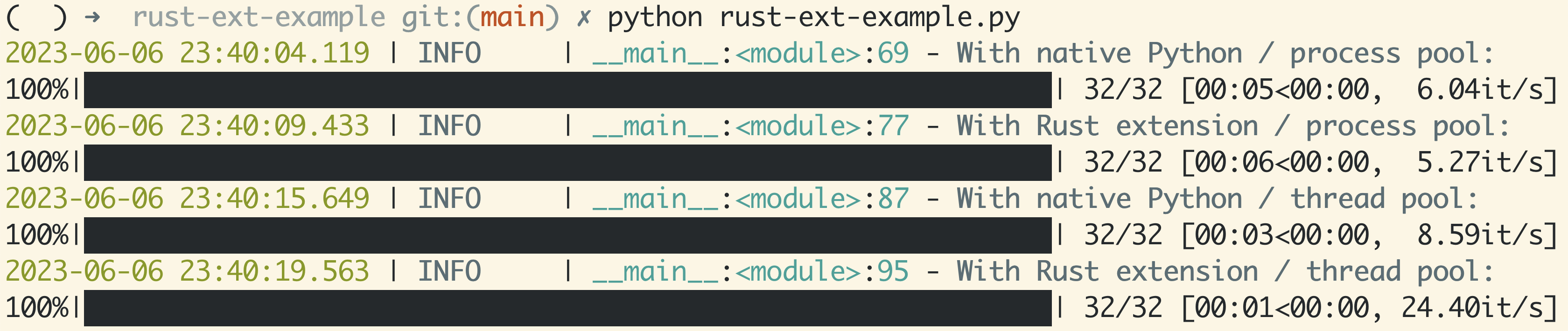

Let’s do a full rerun with a 2x2 combo to take it home:

With Python / process pool:

32/32 [00:05<00:00, 5.45it/s]

With Rust extension / process pool:

32/32 [00:05<00:00, 5.51it/s]

With Python / thread pool:

32/32 [00:03<00:00, 8.21it/s]

With Rust extension / thread pool:

32/32 [00:00<00:00, 33.58it/s]

Closing Thoughts

Before being able to write Python extensions in Rust, I always resorted to workarounds, like using process workers to unlock multicore usage, and paying for their overheads. For this specific task, it used to take me three full days to ingest tens of billions of entries into a database, and I needed to do it many times for experimentation. Now, it can be as short as one single day, a much faster turnaround, leading to more active experimentation loops and bigger findings. I have finally found a powerful alternative, embracing the full potential of performance computing with the mighty combo - Python and Rust. I know for a fact this is going to be the start of something special, and hope you feel the same.