Pools and Pipeline with Tokio (Part II - Streaming)

Dec 28, 2023

You can check out the code here.

In Part I of this mini-series, I implemented an actor pool pattern to perform IO-intensive pipeline jobs using the RPC model. The RPC model is relatively easy to program, because the main control flow code is together in one place, which abstracts away the dependencies as services. I don’t know about you, but this paradigm makes me feel like I’m following along in the life cycle of each task, and unless I send a request to some service, nothing moves. There is a psychological sense of safety to it… The biggest downside used to be spawning threads, which is expensive in synchronous programming. However, with async coroutines, it’s less of an issue.

The Streaming Model

Compare this with the streaming model. By that I mean the worker pool exposes send() and recv() methods, behaving like a processing queue. One single caller could keep calling send() sequentially, and tasks get sent off to the worker pool by a bounded input queue/channel and processed in parallel. The caller is not spawning anything but just sending messages. Then, the results would be sent to a bounded output queue within each worker. There is another coroutine/thread that catches the results from the output queue, like what we did in Part I. The queues are bounded, so the task sender feels the back pressure without needing a semaphore. When dealing with multiple worker pools in stages, we spin up connector coroutine/threads that carry tasks from last pool’s output queue to the next pool’s input queue. The input and output messages both contain unique markers, and we handle errors at the connectors and final output receiver.

How does this make you feel? It feels more dynamic and fluid to me, and the composition of the control flow is spread across connectors and receivers. However, this model maps more idiomatically to a pipeline with separate stages represented as boxes on a flow chart, and we imagine tasks flow through these boxes like a stream. It’s a more natural representation than the RPC model for data processing.

Let us revisit the example from Part I, customized to the streaming model. There are more changes than simply converting an ActorHandle to an ActorPool. First the messages and the error. We now have two message types, one for input, and the other for output. We need to encode a unique identifier to each input/output message, such as a sequential number to keep track of them. We also need a custom error type with the unique identifier to encapsulate the errors handling the task. For simplicity’s sake, I converted the original ActorMessage into a struct from an enum. There is no oneshot channel needed because the output is sent through the output channel.

use log::error;

use thiserror::Error;

pub struct MyActorInputMessage {

pub idx: u64,

}

pub struct MyActorOutputMessage {

pub idx: u64,

pub data: u32,

}

#[derive(Error, Debug)]

#[error("Actor error: {idx}")]

pub struct MyActorError {

pub idx: u64,

}

Then, we implement the private MyActor. It takes the receiver part of the input channel, and the sender part of the output channel. In handle_message(), we evaluate an async task, and map_err whatever errors the underlying business logic code surfaces to our own error type. Over time, this error type will grow more complicated, maybe into an enum with variants that are of interest to the receiving party. The output is a Result type.

struct MyActor {

in_receiver: async_channel::Receiver<MyActorInputMessage>,

out_sender: async_channel::Sender<Result<MyActorOutputMessage, MyActorError>>,

next_id: u32,

}

impl MyActor {

fn new(

in_receiver: async_channel::Receiver<MyActorInputMessage>,

out_sender: async_channel::Sender<Result<MyActorOutputMessage, MyActorError>>,

) -> Self {

MyActor {

in_receiver,

out_sender,

next_id: 0,

}

}

async fn handle_message(&mut self, msg: MyActorInputMessage) {

let MyActorInputMessage { idx } = msg;

self.next_id += 1;

let next_id = self.next_id;

let res = async move {

tokio::time::sleep(tokio::time::Duration::from_millis(500)).await;

anyhow::Ok(MyActorOutputMessage { idx, data: next_id })

}

.await

.map_err(|e| {

error!("MyActor: idx {}: error: {}", idx, e);

MyActorError { idx }

});

// The `let _ =` ignores any errors when sending.

//

// This can happen if the `select!` macro is used

// to cancel waiting for the response.

let _ = self.out_sender.send(res).await;

}

async fn run(&mut self) {

while let Ok(msg) = self.in_receiver.recv().await {

self.handle_message(msg).await;

}

}

}

Then the streaming actor pool. It takes the sender part of the input channel, and the receiver part of the output channel. There is a send() that creates an input message and sends to the input channel. We propagate the async_channel::SendError to the caller, because the request-response cycle is no longer tightly coupled, and it’s good for the caller to know immediately what’s wrong. There is a recv() that forwards the Result to the receiving party. Note we convert the Result<(), async_channel::RecvError> into an Option<()> with .ok() to create a little more clarity. We don’t have graceful shutdown yet, but when we do, None will indicate there are no more messages and the pool is shut down.

pub struct MyActorStreamerPool {

in_sender: async_channel::Sender<MyActorInputMessage>,

out_receiver: async_channel::Receiver<Result<MyActorOutputMessage, MyActorError>>,

}

impl MyActorStreamerPool {

pub fn new(num_actors: usize) -> Self {

let (in_sender, in_receiver) = async_channel::bounded(8);

let (out_sender, out_receiver) = async_channel::bounded(8);

for _ in 0..num_actors {

let in_receiver = in_receiver.clone();

let out_sender = out_sender.clone();

tokio::spawn(async move { MyActor::new(in_receiver, out_sender).run().await });

}

Self {

in_sender,

out_receiver,

}

}

pub async fn send(

&self,

idx: u64,

) -> Result<(), async_channel::SendError<MyActorInputMessage>> {

let msg = MyActorInputMessage { idx };

self.in_sender.send(msg).await

}

pub async fn recv(&self) -> Option<Result<MyActorOutputMessage, MyActorError>> {

self.out_receiver.recv().await.ok()

}

}

Control Flow

Now let’s look at how we wire them together. We use the pool itself, and the Result from the output channel. The input message is not needed directly, because send()’s signature takes care of that for us. We need the pool in a spawned task to send messages sequentially, and in the foreground task, we get into a loop to wait on the messages from the output channel. We handle the Result by a match.

use pools_and_pipeline::my_streamer_pool::{MyActorError, MyActorOutputMessage, MyActorStreamerPool};

const N_TASKS: u64 = 8;

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() {

// create pool

let pool = std::sync::Arc::new(MyActorStreamerPool::new(4));

// submit tasks

let pool_ = pool.clone();

tokio::spawn(async move {

for idx in 0..N_TASKS {

pool_

.send(idx)

.await

.expect("Failed to send message to pool");

}

});

// wait for all tasks to finish

loop {

let t = tokio::time::Instant::now();

let Some(res) = pool.recv().await else {

break;

};

match res {

Ok(MyActorOutputMessage { idx, data }) => {

println!("{idx} ended in {}ms", t.elapsed().as_millis());

println!("idx {}: data: {}", idx, data);

}

Err(MyActorError { idx }) => {

println!("{idx} ended in {}ms", t.elapsed().as_millis());

println!("idx {}: error", idx);

}

}

}

}

In Part I, we #[derive(Clone)] earlier on the MyActorPool. Cloning the pool is really cloning the channels the pool owns. To be more clear, here we skip the derive, but instead wrap the pool around an Arc. This makes the relationship more explicit. This is also essential to implement graceful shutdown, which we will visit later.

Let’s run it. We see that ~500ms only showed up twice, and the rest are 0ms. It means tasks are running in parallel by all workers. Again, we haven’t implemented graceful shutdown yet, so we need to CTRL+C out of the loop.

3 ended in 502ms

idx 3: data: 1

2 ended in 0ms

idx 2: data: 1

1 ended in 0ms

idx 1: data: 1

0 ended in 0ms

idx 0: data: 1

7 ended in 501ms

idx 7: data: 2

4 ended in 0ms

idx 4: data: 2

6 ended in 0ms

idx 6: data: 2

5 ended in 0ms

idx 5: data: 2

^C

Graceful Shutdown

On a high level, how does graceful shutdown work? Recall the webserver example from the Book, when things involve channels, usually dropping all clones of one side would prompt the other side to receive a None or Err, exiting out of the loop. How can we do that here?

We hold two clones of the pool object, one for the sending party, and the other for the receiving party. With data processing, the sending party usually knows when the source is finished. So we should drop from the sending party. We need to implement a close() method for the pool, that somehow drops the input channel sender. The private MyActors would break out of their own loops, dropping the output channel sender. Finally the pool’s recv() call will break out of its loop. This is done through wrapping the Senders in Options, and calling take() to swap them out to drop.

The private MyActor:

struct MyActor {

in_receiver: async_channel::Receiver<MyActorInputMessage>,

out_sender: Option<async_channel::Sender<Result<MyActorOutputMessage, MyActorError>>>,

next_id: u32,

}

impl MyActor {

fn new(

in_receiver: async_channel::Receiver<MyActorInputMessage>,

out_sender: async_channel::Sender<Result<MyActorOutputMessage, MyActorError>>,

) -> Self {

MyActor {

in_receiver,

out_sender: Some(out_sender),

next_id: 0,

}

}

async fn handle_message(&mut self, msg: MyActorInputMessage) {

let MyActorInputMessage { idx } = msg;

self.next_id += 1;

let next_id = self.next_id;

let res = async move {

tokio::time::sleep(tokio::time::Duration::from_millis(500)).await;

anyhow::Ok(MyActorOutputMessage { idx, data: next_id })

}

.await

.map_err(|e| {

error!("MyActor: idx {}: error: {}", idx, e);

MyActorError { idx }

});

match &self.out_sender {

// The `let _ =` ignores any errors when sending.

//

// This can happen if the `select!` macro is used

// to cancel waiting for the response.

Some(out_sender) => {

let _ = out_sender.send(res).await;

}

None => {

error!("MyActor: idx {}: error: pool is closed.", idx);

}

}

}

async fn run(&mut self) {

while let Ok(msg) = self.in_receiver.recv().await {

self.handle_message(msg).await;

}

self.out_sender.take();

}

}

The MyActorStreamerPool:

pub struct MyActorStreamerPool {

in_sender: Option<async_channel::Sender<MyActorInputMessage>>,

out_receiver: async_channel::Receiver<Result<MyActorOutputMessage, MyActorError>>,

}

impl MyActorStreamerPool {

pub fn new(num_actors: usize) -> Self {

let (in_sender, in_receiver) = async_channel::bounded(8);

let (out_sender, out_receiver) = async_channel::bounded(8);

for _ in 0..num_actors {

let in_receiver = in_receiver.clone();

let out_sender = out_sender.clone();

tokio::spawn(async move { MyActor::new(in_receiver, out_sender).run().await });

}

Self {

in_sender: Some(in_sender),

out_receiver,

}

}

pub async fn send(

&self,

idx: u64,

) -> Result<(), async_channel::SendError<MyActorInputMessage>> {

let msg = MyActorInputMessage { idx };

match &self.in_sender {

Some(in_sender) => in_sender.send(msg).await,

None => Err(async_channel::SendError(msg)),

}

}

pub async fn recv(&self) -> Option<Result<MyActorOutputMessage, MyActorError>> {

self.out_receiver.recv().await.ok()

}

pub fn close(&mut self) {

self.in_sender.take();

}

}

This is where wrapping MyActorStreamerPool with Arc is key to graceful shutdown. When we call close(), we need to make sure it acts on the very same MyActorStreamerPool that is doing the recv(). Otherwise, not all clones of the input channel Sender are dropped, and shutdown wouldn’t happen.

Also notice close() needs a &mut self, so in calling with Arc, we need internal mutability. So we need either a Mutex or RwLock. Would that slow down regular message passing because every action has to be protected by a lock? Luckily for us, in this case both send() and recv() of the async-channel only need a non-mutable &self. I looked into other crates, neither Flume, or the sync world Crossbeam require these methods to take &mut self. There must be a reason for this “luck”, but I haven’t looked deeper into it. Let’s just take advantage of it now! With simply a RwLock, we can incur minimal locking, only when close() is called.

Now the async main becomes:

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() {

// create pool

let pool = std::sync::Arc::new(tokio::sync::RwLock::new(MyActorStreamerPool::new(4)));

// submit tasks

let pool_ = pool.clone();

tokio::spawn(async move {

for idx in 0..N_TASKS {

pool_

.read()

.await

.send(idx)

.await

.expect("Failed to send message to pool");

}

println!("All tasks submitted. Closing pool.");

pool_.write().await.close();

});

// wait for all tasks to finish

let mut res_all = vec![];

loop {

let t = tokio::time::Instant::now();

let Some(res) = pool.read().await.recv().await else {

break;

};

match res {

Ok(MyActorOutputMessage { idx, data }) => {

println!("{idx} ended in {}ms", t.elapsed().as_millis());

res_all.push(data);

}

Err(MyActorError { idx }) => {

println!("{idx} ended in {}ms", t.elapsed().as_millis());

println!("idx {}: error", idx);

}

}

}

println!("res_all = {:?}", res_all);

}

And the output looks like:

All tasks submitted. Closing pool.

3 ended in 502ms

0 ended in 0ms

1 ended in 0ms

2 ended in 0ms

7 ended in 502ms

4 ended in 0ms

6 ended in 0ms

5 ended in 0ms

res_all = [1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2]

Potential Customizations

There are a few potential points of adaptation. One is, you might not want to close the pool to break out of the receiver loop. In that case, you might also know how many tasks the sender would send. So just count to that and break. You are able to reuse the pool this way, but also responsible for making sure different occasions of using the pool won’t interfere with each other.

Another consideration: the sender might hold a source that is !Send (like many iterators from Itertools), which means it is not able to be sent between threads across an .await. This could be solved with spawn_local(), or a current_thread runtime. But maybe the simplest approach for this iterator source scenario (it’s mildly blocking anyway) is a sync send_blocking() API (supported by async-channel and Flume), coupled with spawn_blocking(). Note we also need the sync version std::sync::RwLock instead of tokio::sync::RwLock for it.

// impl MyActorStreamerPool {

pub fn send_blocking(

&self,

idx: u64,

) -> Result<(), async_channel::SendError<MyActorInputMessage>> {

let msg = MyActorInputMessage { idx };

match &self.in_sender {

Some(in_sender) => in_sender.send_blocking(msg),

None => Err(async_channel::SendError(msg)),

}

}

pub fn recv_blocking(&self) -> Option<Result<MyActorOutputMessage, MyActorError>> {

self.out_receiver.recv_blocking().ok()

}

// }

// async fn main() {

// submit tasks

let pool_ = pool.clone();

tokio::task::spawn_blocking(move || {

for idx in 0..N_TASKS {

pool_

.read()

.unwrap()

.send_blocking(idx)

.expect("Failed to send message to pool");

}

println!("All tasks submitted. Closing pool.");

pool_.write().unwrap().close();

});

// }

It’s kind of magical that all these can work, right? Rust and Tokio are so flexible and as long as the code compiles, you are almost there with a safe program that will run until the job is finished. Simply amazing!

One other potential adaptation is returning the results in the original order, in a streaming way, without first hoarding up all the results. This is similar to the very useful multiprocessing.Pool.imap. You could borrow the logic from here in the pool’s recv(). Not going more into it, but briefly, you need a next_index counter, another pair of Sender and Receiver, and a HashMap; at pool init, you spawn a task in the background that constantly reorders the results from the raw out_receiver and sends through that extra Sender. If you wish to reuse the pool, you also need a reset_next_index() method to clear the counter state. There are a lot of states, and depending on the order of results, you might end up hoarding a lot of memory anyway. There may be a better way to do it.

Full Program

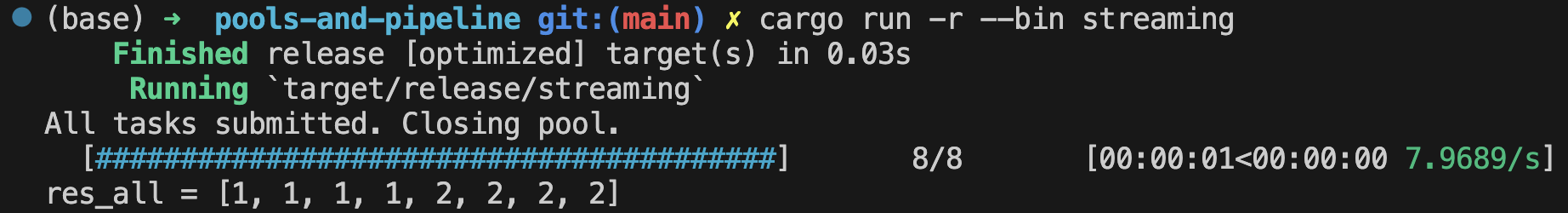

Finally, with the bells and whistles like in Part I, this is the main program:

use indicatif::{ProgressBar, ProgressStyle};

use pools_and_pipeline::my_actor_streamer_pool::{

MyActorError, MyActorOutputMessage, MyActorStreamerPool,

};

use pools_and_pipeline::utils::InterruptIndicator;

use std::sync::Arc;

use tokio::sync::RwLock;

const N_TASKS: u64 = 8;

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() {

// attach CTRL+C handler

let interrupt_indicator = InterruptIndicator::new();

// make pretty progress bar

let pb = ProgressBar::new(N_TASKS);

let sty = ProgressStyle::with_template(

"{spinner:.cyan} [{bar:40.cyan/blue}] {pos:>7}/{len:7} [{elapsed_precise}<{eta_precise} {per_sec:.green}] {msg}"

).unwrap().progress_chars("#>-");

pb.set_style(sty);

// create pool

let pool = Arc::new(RwLock::new(MyActorStreamerPool::new(4)));

// submit tasks

let pool_ = pool.clone();

tokio::spawn(async move {

for idx in 0..N_TASKS {

if interrupt_indicator.is_set() {

println!("Interrupted! Exiting gracefully...");

break;

}

pool_

.read()

.await

.send(idx)

.await

.expect("Failed to send message to pool");

}

println!("All tasks submitted. Closing pool.");

pool_.write().await.close();

});

// wait for all tasks to finish

let mut res_all = vec![];

loop {

let t = tokio::time::Instant::now();

let Some(res) = pool.read().await.recv().await else {

break;

};

match res {

Ok(MyActorOutputMessage { idx: _idx, data }) => {

res_all.push(data);

}

Err(MyActorError { idx }) => {

println!("{idx} ended in {}ms", t.elapsed().as_millis());

println!("idx {}: error", idx);

}

}

pb.inc(1);

}

pb.finish();

println!("res_all = {:?}", res_all);

}

All tasks submitted. Closing pool.

^C⠁ [#####>----------------------------------] 1/8 [00:00:00<00:00:03 1.9906/s]

[########################################] 8/8 [00:00:01<00:00:00 7.9636/s]

res_all = [1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2]

Because of the buffering at the input channel, tasks would run further until gracefully exiting.

Again, you probably want to use Anyhow to handle errors and convert the unwrap() into ? propagation for good measure.

To Conclude

The RPC and streaming models in this series are suitable for more elaborate tasks with actors. They require some boilerplate code to set up, but you get great encapsulation, resource management, and separation of responsibilities. On the other hand, what do you do when you don’t need actors, and the pipeline is mostly stateless? Let’s expore that in another post.