The Wonders of RocksDB in Rust (Part I - Intro)

Feb 10, 2026

You can check out the code here.

Squarely two years ago (Jan 2024), I needed to interact with an in-house K-V store at work, and the underlying DB layer was RocksDB. I had been using and tuning RocksDB in C++ land since 2022 to implement the on-disk Faiss Inverted File index to support our deca-B use case, and spent a good part of 2023 digging my heels into the fast-maturing Rust ecosystem. The natural question was - can I do my data engineering with RocksDB in Rust?

Looking back, I got so much out of that setup, and I still frequently reuse and share with people some of the techniques from that time. This enabled my one-big-machine-style data processing pattern, turning Big Data into smoldata, accelerated by flexibly picking from a fleet of EC2 instances. It’s gotten to a point where a mini blog series is warranted.

Historically, if you want to deal with data in a structured way, you have two more or less isolated options. You either go high-level with packaged database services (OLTP/OLAP, SQL/NoSQL), get locked into their provided transformation functions, and pay the interface overhead. One step down, there are embedded OLTP (SQLite) and OLAP (DuckDB), but they are purpose-built for SQL-centric workloads. On the other end, you roll up your sleeves and reinvent a good part of the wheel from on-disk data representation all the way up. RocksDB filled this gap by providing a strong embedded K-V store for other database services to build upon. But much of the development was confined to the database community, rather than the data engineering community. It was very hard to imagine using systems languages like C/C++ to work on data engineering problems, because one bad pointer may corrupt your data silently, and data outlives software!

Rust changed this. It is a high-level, memory-safe language for your data engineering problems, with performance matching other low-level systems languages. What’s been historically overlooked is now possible, and can give one great leverage. You can actually use Rust to get data in and out of RocksDB as stable and long-term stores!

This Part I just scratches the surface with the state of the ecosystem, basic patterns, parallel reads and writes with performance in mind. It doesn’t go deep into topics that showcase the mojo. We save them for the Part II.

RocksDB and its Bindings

At its core, RocksDB is a C++ project. It comes with Java bindings in the original repo, and you can find bindings for other languages. As of this post’s writing, for Go, linxGnu/gorocksdb is the most up-to-date with the underlying C++ code. For Rust, the rust-rocksdb crate from Zaidoon leads the pack for freshness. The original rocksdb crate from Tyler Neely (spacejam) updates less frequently.

Per Rust ecosystem’s convention, when wrapping code from other languages, it’s split into the high-level and low-level counterparts, two separate crates. The high-level crate takes the more regular name, rust-rocksdb. The low-level crate takes a suffix -sys, in this case, rust-librocksdb-sys. Usually, the low-level crate contains the original code so there is no external dependency to chase outside of cargo. This leads to long compilation times, because the original code needs to compile too. Sometimes, it gives you the option to specify an existing binary distribution on your computer.

How do you know what version of RocksDB it’s wrapping? If you navigate to the Dependencies tab of a certain version (e.g. 0.46.0) of rust-rocksdb, you will find the corresponding version of rust-librocksdb-sys with version string 0.42.0+10.10.1. The main versions, 0.46.0 and 0.42.0 for the two crates don’t tell you anything about the wrapped C++ RocksDB’s version. However, this part after the + sign, 10.10.1, does. Then you can go to facebook/rocksdb’s corresponding tag to find the meat. The wrapper, when it does its job well, should faithfully reflect the features of the wrapped code.

Basic Patterns

This is the basic write and point-lookup pattern (full code):

db.put(key.as_bytes(), val.as_bytes())?;

let value = db.get(key.as_bytes())?;

if let Some(value) = value {

println!("val: {}", std::str::from_utf8(&value)?);

} else {

println!("key not found");

}

Since the underlying data are sorted in an LSM-Tree, we can iterate consecutively (full code):

let mut db_iter = db.full_iterator(IteratorMode::Start);

while let Some(Ok((key, value))) = db_iter.next() {

println!(

"key: {} value: {}",

String::from_utf8_lossy(&key),

String::from_utf8_lossy(&value)

);

}

Parallel Scan

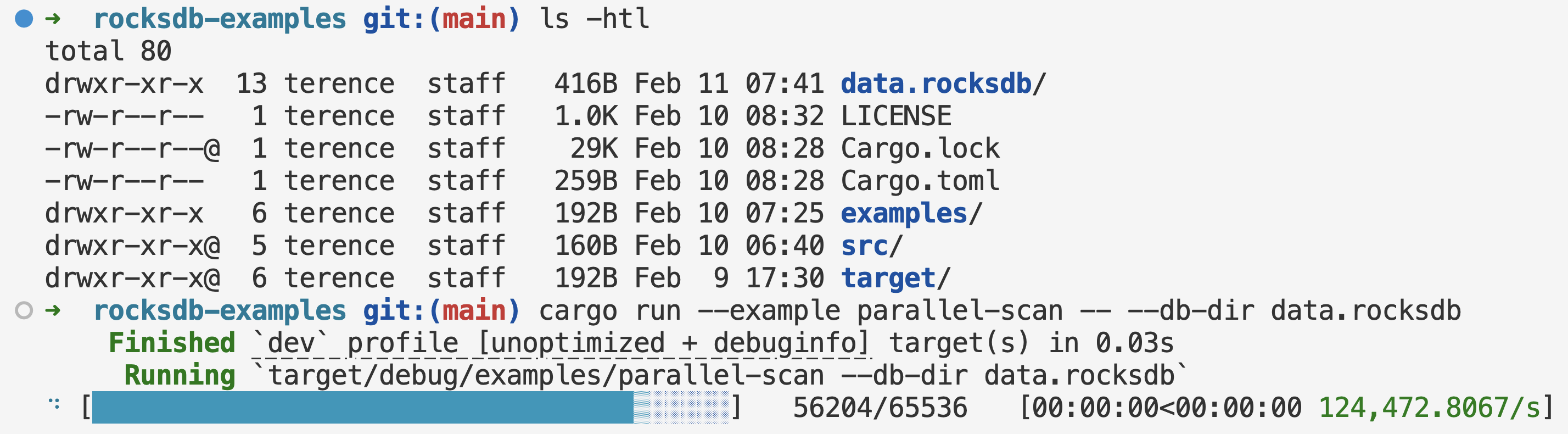

There are a lot of CPU cores on your computer. If you need to scan a substantial portion or the entirety of the database, do this (full code):

let db = open_rocksdb_for_read_only(&args.db_dir, true)?;

let prefixes = generate_consecutive_hex_strings(4);

let count = prefixes

.into_par_iter()

.map(|prefix| {

let prefix = prefix.as_bytes();

let mut db_iter = db.full_iterator(IteratorMode::From(prefix, Direction::Forward));

let mut count = 0;

while let Some(Ok((key, _value))) = db_iter.next() {

if &key[..prefix.len()] != prefix {

break;

}

count += 1;

}

count

})

.reduce(|| 0_usize, |acc, c| acc + c);

The example here has more or less evenly distributed hex strings (emulating hashes) as keys, so one could create consecutive short hex strings with a configurable number of digits, e.g. 4 (generate_consecutive_hex_strings(4)). They look like 0000, 0001, …, f000, …, ffff. Your data might use different formats for keys, and they might not be evenly distributed. However, hashing usually redistributes lexically clustered keys evenly. So consider using them as keys and attaching the original keys as part of the values. Good, fast hashing algorithms for this purpose are murmur3, xxhash.

The parallelization is provided by the excellent rayon crate. .into_par_iter() turns a Vec into a parallel iterator that distributes work across a number of threads in Rayon’s thread pool.

You can put a lot more complex logic in the inner loop, and treat each prefix as the unit of work. Depending on your workload, select the number of digits so that each unit of work is small enough to not cause resource starvation (OOM) or run too long, and big enough to avoid scheduling overhead.

Parallel Bulk Load

If you have many writes, create a WriteBatch and write once (full code):

let mut write_batch = WriteBatch::default();

for _ in 0..ENTRIES {

let key = generate_random_hex_string(RAND_BYTES_LEN);

let val = generate_random_hex_string(RAND_BYTES_LEN);

write_batch.put(key.as_bytes(), val.as_bytes());

}

db.write(&write_batch)?;

Often, you have TBs of data to ingest, and you should leverage those CPU cores. So let’s write the write batches in parallel (full code):

let db = open_rocksdb_for_bulk_ingestion(&args.db_dir, Some(7), None)?;

rayon::ThreadPoolBuilder::new()

.num_threads(NUM_THREADS)

.build_global()?;

(0..NUM_THREADS).into_par_iter().for_each(|_| {

let mut write_batch = WriteBatch::default();

for _ in 0..ENTRIES_PER_THREAD {

let key = generate_random_hex_string(RAND_BYTES_LEN);

let val = generate_random_hex_string(RAND_BYTES_LEN);

write_batch.put(key.as_bytes(), val.as_bytes());

}

db.write_without_wal(&write_batch).unwrap();

});

db.flush()?;

There are a few things here. We configure each thread to write all data entries into a write batch before writing the batch into the DB. This is just an example writing random hex strings. In real work, you should choose a small but chunky parallelization granularity to accumulate the write batches.

We also write without recording entries in the Write-Ahead Log (WAL), so they only go into the memtables. We flush the memtables at the very end. This avoids the extra work of writing to the WAL, at the risk of the bulk load job crashing in the middle. Usually, it’s not worth resuming during a bulk load, and you can just redo completely.

When opening the DB, there are many options to control the behavior of the session while the DB is open. Some options affect reads over existing data in sorted string table (SST) files, while some options affect the new files written. RocksDB is known to be production-ready, highly tunable, and highly backward-compatible. Generally, newer versions can open DBs created from older versions. Some older versions can open DBs created from newer versions. To learn more about this and become an expert, it’s important to read through the Wiki, the FAQ, and read the header files options.h (and table.h, advanced_options.h) / Rust bindings docs.

If you want a head start, look at the various open_rocksdb_*() functions in my rocksdb_utils.rs. It gives you a very strong baseline on modern SSDs.

Compaction After Bulk Load

After a bulk load without compaction, you need to manually compact the DB (full code):

let mut compaction_opts = rust_rocksdb::CompactOptions::default();

compaction_opts.set_exclusive_manual_compaction(true);

compaction_opts.set_change_level(true);

compaction_opts.set_target_level(ROCKSDB_NUM_LEVELS - 1);

compaction_opts

.set_bottommost_level_compaction(rust_rocksdb::BottommostLevelCompaction::ForceOptimized);

db.compact_range_opt(None::<&[u8]>, None::<&[u8]>, &compaction_opts);

This takes a while, and roughly doubles your disk usage. If you use zstd as the bottommost level, it will be less than doubling. It gradually approaches that peak disk usage, and very quickly drops to the final size by deleting old files. If anything fails in this process, such as running out of disk space, abrupt cancellations, or server crashes, the DB is still OK. RocksDB is used as the embedded layer for many production DB services, and is built rock-solid in its default configuration without turning on risky knobs. It has checksums all over the place to detect errors.

Why is RocksDB in Rust a strong setup for data engineering? It’s an embedded, production-grade K-V store without the overhead of a full database service, coupled with a memory-safe language. With the techniques above, you can already move a lot of data in and out of RocksDB. In Part II and Part III, we’ll look at some very cool patterns, including parallel two-pointer set operations, and MapReduce for out-of-core aggregations.