Some AWS EC2 Instance Choices

Jan 23, 2026There are many aspects of AWS EC2 instances. AWS offers a whole fleet of different varieties, targeting a wide range of use cases. It’s a big topic, and one should probably have a conversation with their AI friend and learn as they experiment with a few different scenarios if they want to get a better grounded sense.

Over the years, I have used a few families of instances at length. So here are some of my personal notes.

The t Family

They are burstable instances. The smaller ones are often offered for free as the starter plan for your EC2 journey. You can host bursty web servers on them. I don’t use them as much. They are about 14% cheaper compared to same-gen/spec m instances. e.g. t3.large vs m5.large (both Intel Skylake), and t4g.large vs m6g.large (both AWS Graviton2). The generation numbers are simply zigzagged.

The c/m/r Families

They are the workhorse instances, with CPU/RAM ratio of 1:2, 1:4, and 1:8. You’d usually use c when you have compute-heavy workloads, with native languages C/C++/Rust. You’d use m when you use interpreted languages such as Python for web servers, and want to be on the safe side. You’d use r when you want to host a database that requires a good amount of caching, or in-memory data structures, like vector DBs.

It’s important to think about CPU and RAM differently as resources. CPU cores accelerate things, and with more, you get to do things faster, but they are more or less elastic. On the other hand, RAM is usually a rigid requirement - your application might just crash due to OOM if there is not enough memory. Swapping on fast local NVMe drives could alleviate some hot spots occasionally, but the data structures that work well on RAM usually don’t work that well on drives, even NVMe drives, due to random access patterns (it’s what RAM is literally named after). Because of this, when you host databases on r instances, and your traffic is low, you might observe the CPUs are just idling at 5% - kind of a waste.

You could consider the lower-power processor options, like choose r6a (AMD Zen 3) at a 10% discount, or r6g (AWS Graviton2) at a 20% discount compared to same-gen r6i (Intel Ice Lake). Their lower prices reflect the lower performance pretty accurately, so you get what you paid for. Note that *6a instances have AMD Zen 3 chips that don’t come with later SIMD instruction sets (notably AVX-512) but just AVX2. In comparison, *6i instances have Intel Ice Lake chips that do have AVX-512 for your hashing/vector calculations. You do have to compile your code specifically to support these SIMD instructions, or trust some pre-compiled binaries. I would ask you to migrate away from *5 instances, because they cost exactly the same as *6i instances and have Intel Skylake chips that also don’t have AVX-512, only AVX2.

Arm chips require your code/containers to be compiled for them and able to run on them. Nowadays it’s increasingly not a problem in containerized environments. In terms of SIMD support, AWS Graviton2 (ARMv8.2-A) and beyond chips all have NEON instruction sets (typically 128-bit width), but they are a lot weaker than AVX2 (256-bit width)/AVX-512 (512-bit width). Later Arm chips like AWS Graviton3 (ARMv8.4-A) and Graviton4 (ARMv9-A) have wider bit width SIMD instructions (256-bit SVE and 512-bit SVE2 respectively). These are actively becoming more competitive, but the code that uses these advanced instruction sets is only getting started.

Newer Generations

The storytelling and price performance shift quite significantly at *7* and *8* generations in recent years. This is where AMD and AWS’s own Gravitons really took the lead. For AMD, *7a (Zen 4) and *8a (Zen 5) added AVX-512, and (drum roll…) removed Hyper Threading (HT). So each vCPU is pound per pound a real core, instead of *5- and *6*-era Intel/AMD HT. This resolved a minor but annoying quirk when you watched your compute-heavy workloads starting to thrash as CPU utilization reached just 50% with HT… No more! As a result, the nominal sticker prices for AMD chips are ~15% higher than same-gen Intel chips, e.g. c7a.large vs c7i.large. But you get double the physical cores! This is actually insane! *7* Graviton3 chips narrowed the price difference (18%) to same-gen Intel chips, and *8* Graviton4 chips did that further (15%). I personally ran some workloads on big c8a.48xlarge and c8g.48xlarge boxes. I gotta tell ya, they are nice. Note that, because of HT, Intel could put out a c8i.96xlarge, but at high compute load they are effectively 192 instead of 384 physical cores.

Variations

There are these suffixes to the instance names, like d for extra and smallish ephemeral NVMe drives attached if your workloads need them, and n for much higher networking allowance. They could come in combos, e.g. m6i, m6id, m6in, m6idn. However, with the *7* and *8* generations, AWS moved away from Intel chips to prefer their own Gravitons to be the bearer of these varieties. They are also not evenly distributed in the c/m/r spectrum. In *7g, c7g has d and n, but m7g/r7g only have d. *8g has a much fuller line-up, and introduced another variation b for higher EBS volume allowance. I would like to note that n (and aforementioned b) gives you much better EBS volume communication capacity (IOPS and throughput), because EBS volumes are network-connected drives, so they follow similar rules. You need to be aware of this when your database needs larger than usual communication bandwidth than what regular instances have to offer. So upgrade with n and b accordingly.

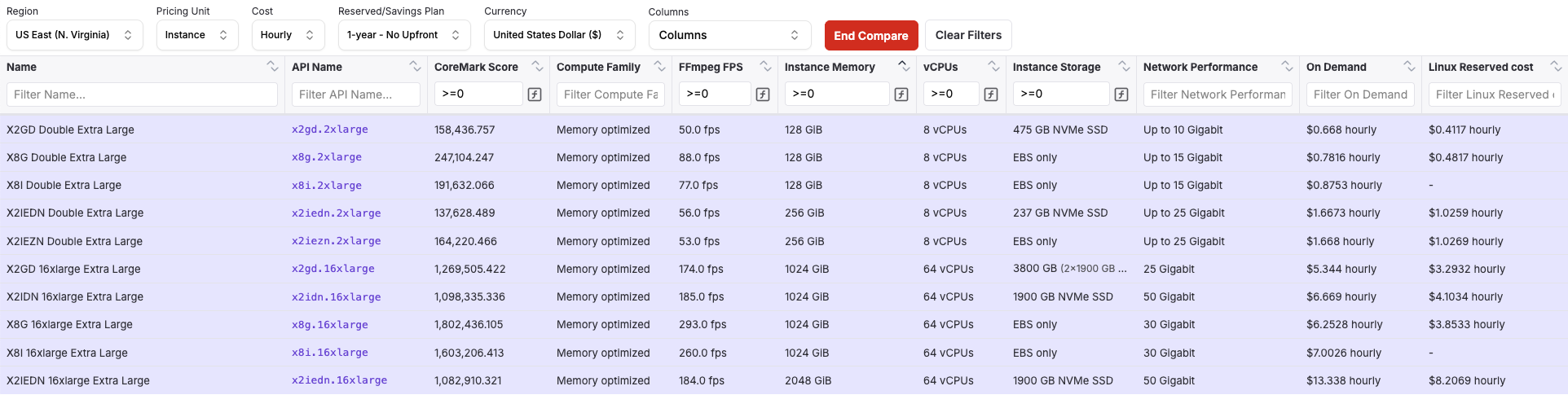

The x Family

Historically you don’t see these often. They are at the right side of the r family with even bigger CPU:RAM ratios 1:16 and 1:32. There were x1*/x2*, and they jumped to x8 to align the generation numbers. Here is a list.

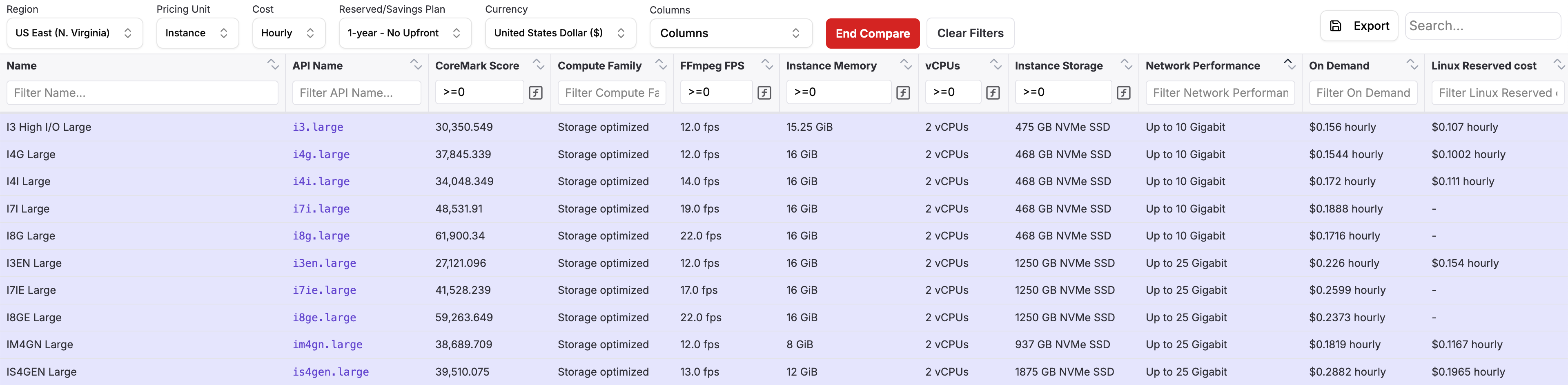

The i Family

They come with big numbers of ephemeral NVMe drives (“storage optimized”) than d-suffixed instances. They are very helpful if you have a 50TB database shard to operate on. i4i/i3en used to be the Intel choices, and i4g/im4gn/is4gn used to be the Graviton2 choices. And then things moved strategically, jumping generations. It’s a little inconsistent to explain, so here I link a list down here.

Notably, with these latest i7ie.48xlarge and i8ge.48xlarge instances, you get a whopping 120TB worth of NVMe drives! You can RAID0 them to do large-scale data processing within a single instance. Your Big Data problems suddenly became smoldata problems that just need to be paired with a fast programming language. I wrote a big post about it - Big Data Engineering in the 2020s - One Big Machine. I hope you enjoy that read too.

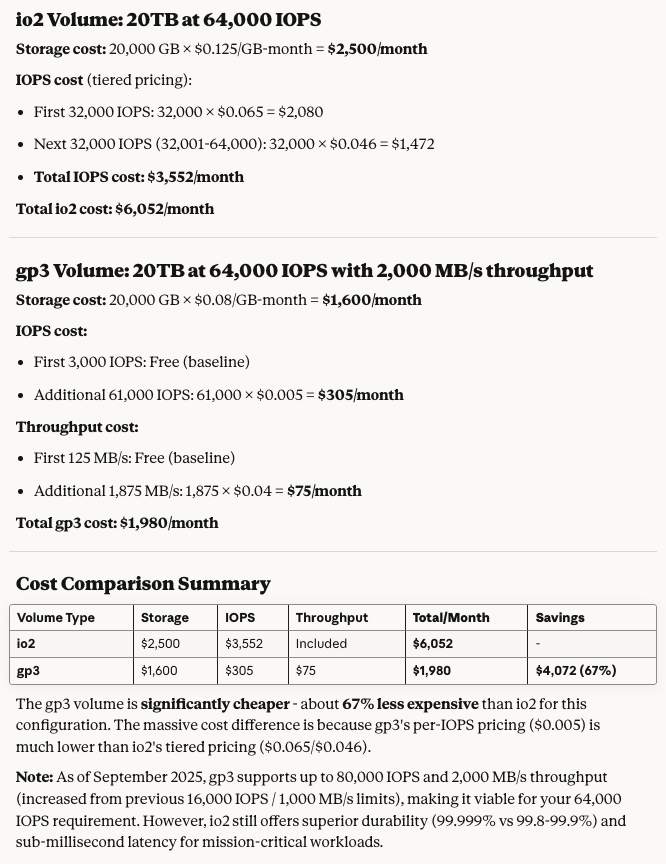

Another point to make is, compare r7i.24xlarge ($6.35/hr on demand), i7i.24xlarge ($9.061/hr with 22.5TB NVMe), and i7ie.24xlarge ($12.475/hr with 60TB NVMe). They all have the same basic CPU/RAM specs. If you take similar EBS gp3 drives and amp up the IOPS and throughput to max (80k IOPS and 2GB/s throughput since Sep 2025), 22.5TB is around $2000/mo ($2.8/hr), and 60TB is around $5000/mo ($7/hr). Of course, EBS gp3 volumes are way slower than local NVMe drives, so they are not really a fair comparison, but often a practical one in terms of deployment. And see, the extra disk cost almost add up exactly from the r7i.24xlarge base! I thought it’s an interesting fact to share.

The thing about these instances and local ephemeral NVMe drives, is that they get wiped and reprovisioned to someone else once you power down the machine. They are fine if you restart them though. If you intend to run actual monstrous database workloads on them (like with ScyllaDB), you need to stay on top of data backup & restore, and have a run book, because they are less on durable media than EBS drives such as gp3 and io2.

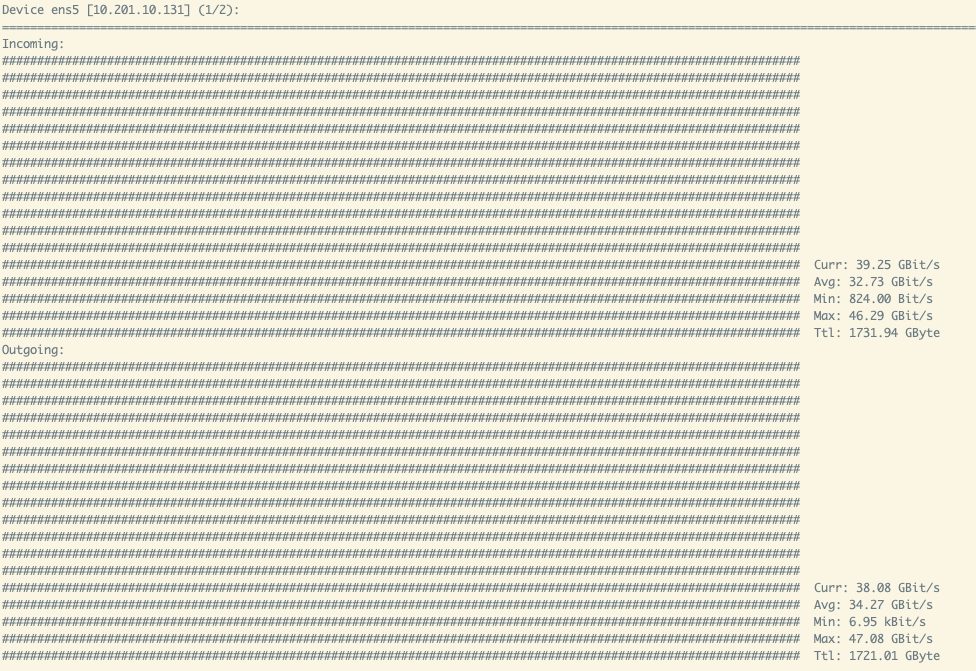

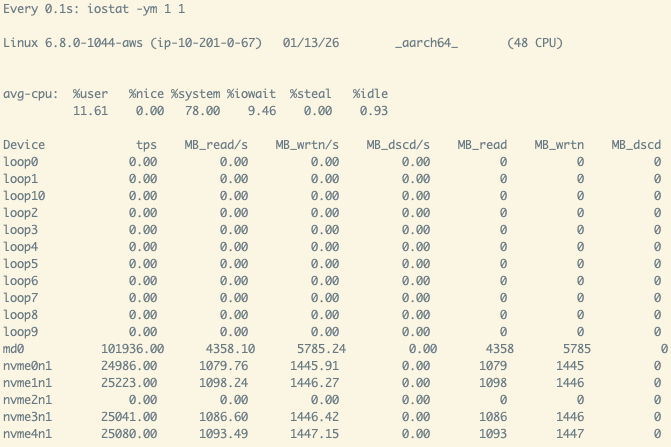

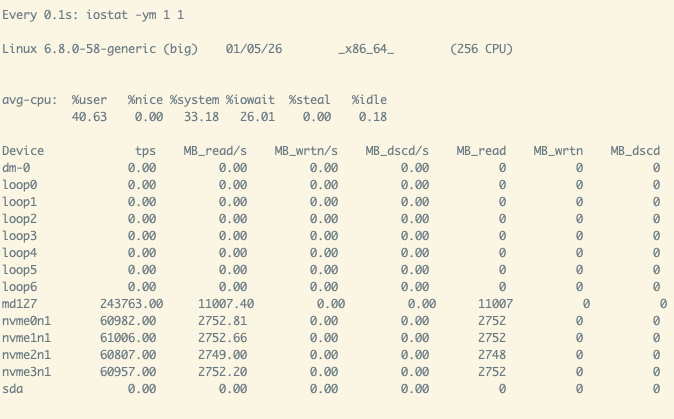

That said, the other thing about these instances and local ephemeral NVMe drives… is that they are monstrously fast:

|

|

People that get into databases, ML/AI, and systems programming on AWS often get tripped by the slow disks and get throttled hard. I hope you try these instances.

g4dn/g5/g6/g6f

They are the family of NVIDIA inference-oriented cards. g4dn has NVIDIA T4, g5 has A10g, and g6/g6f has L4. Interestingly, g6 (L4) is less powerful than g5 (A10g), and priced lower. g6f is a new savers option featuring fractionals of a L4 GPU, benefiting from NVIDIA’s GPU partitioning.

p3 (going away)/p4d/p5/p6

They are the family of NVIDIA training-oriented cards. p3 had NVIDIA V100, p4d has A100, p5 has H100, and p6 has B200/B300/GB200. If you are not a large company and have signed a big deal with them, or 3y savings plans, don’t use them. Go somewhere else. This is a hot topic, and deserves its own post. I gotta say for a lot of non-LLM workloads, there are A100s around in various market segments, and the new RTX Pro 6000 Blackwell cards are awesome. This is a fast-moving and fast-expiring situation, so we can look back in a year.

g6e/g7e

These are in fact in the middle between training and inference, targeting GPU (virtual) workstations. g6e has L40S, and g7e in fact has RTX Pro 6000 Blackwell. I didn’t know about them until writing this post.

There are other families, like u for extreme CPU/RAM ratio, hpc* for HPC parallel scientific workloads, mac* for MacOS CI/CD purposes, inf* and trn* for AWS’s own Inferentia and Trainium chips, and more. I have not directly used them yet. Although, the dl1.24xlarge (Intel’s Habana Gaudi training chip) on AWS Marketpace paved my way to directly contact the Habana team to use their Gaudi2 chips for a few months, and got great training results after jumping through a few hurdles.

EBS News

One last thing of note - back in Sep 2025, AWS announced their gp3 EBS volumes got a lot better. It was fantastic news to me for some workloads that I had to run on expensive io2 drives. Buying IOPS for io2 is extremely expensive, but very cheap for gp3.

Just going to end it here…