A Week of Rust

Mar 21, 2023

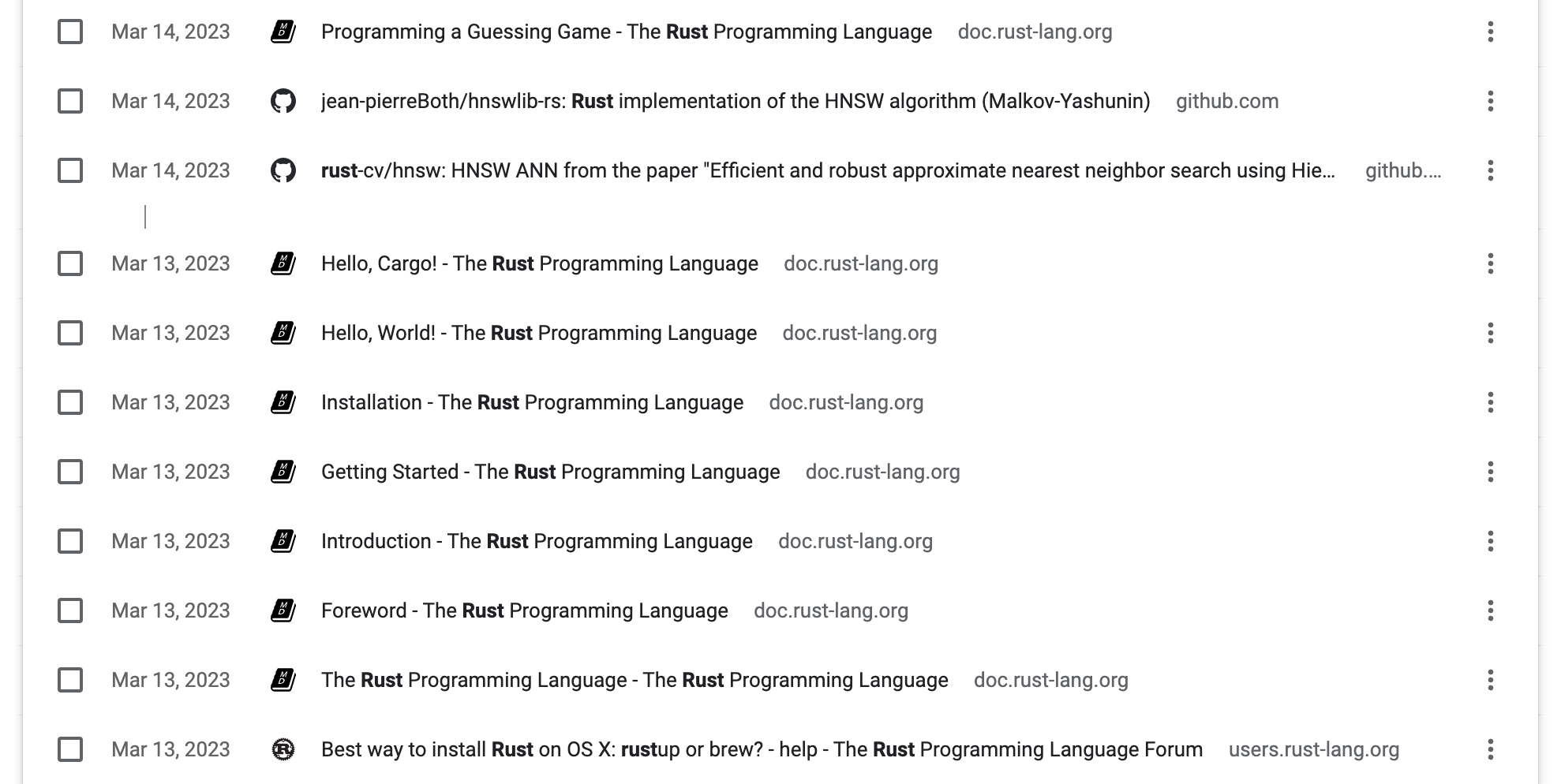

The stars are aligned. I finally sat down and went through “the book.”

I tweaked the color combo to “Rust” and went through the first eight chapters slowly and carefully, ending in Common Collections and, in addition, Chapter 15. Smart Pointers. Typically learning to program is best to be hands-on for me, coupled with many random detours. However, I found the structure and flow of this book very helpful, explaining the necessary details while staying in context, and I enjoyed following its lead. I would attribute this partly to the writing style, with focused code demonstrations iteratively simulating the debugging process one would go through themselves. One would also realize it’d be necessary to sit through the “lecture” sections before preemptively getting hands dirty in an editor with Rust because of the philosophy and design decisions that led to the creation of this language - they need more words to be clear.

This book was written for experienced programmers with a few other languages under their belts. As of today, I think most programmers embarking on learning Rust are from the C++ land. Like C++, Rust was designed as a systems language that aimed to be extremely efficient (zero-cost abstraction). So as a user, you must pay attention to resource management, notably RAII (vs garbage collection in other popular languages), copying vs referencing, etc. But it also aims to solve issues practitioners of C++ have struggled with at scale regarding memory safety (undefined behavior, segmentation fault). This imposes much unexpectedness on programmers at various levels.

I wrote about my programming journey in a separate post. Long story short, I had enough exposure to C++-style resource management and found it instrumental to my learning of Rust. If you come from other backgrounds, your mileage will differ. There was a synthesis of properties from other languages into Rust, and I found myself returning to the C++ mental box for comparisons the most. Here I would like to highlight the parts I found note-worthy.

Eager Moves

In C++, when you assign a variable to another variable, the value is copied. With most standard library copiable types that manage resources, this leads to pretty extensive copies. Smart pointers such as shared_ptr are exceptions. Generally, you would need to explicitly use std::move() to get an rvalue reference (see later) to invoke the C++11 move semantics.

vector<int> v1 = {1, 2, 3};

// this copies the entire vector

vector<int> v2 = v1;

string s1 = "hello";

// this copies the entire string

string s2 = s1;

In Rust, when you assign a variable to another variable, the value is moved, if it does not implement the Copy trait. This is a very different behavior from C++.

let v1 = vec![1, 2, 3];

// this moves the entire vector

let v2 = v1;

println!("v2 = {:?}", v2);

// println!("v1 = {:?}", v1); // error: use of moved value: `v1`

let s1 = String::from("hello");

// this moves the entire string

let s2 = s1;

println!("s2 = {}", s2);

// println!("s1 = {}", s1); // error: use of moved value: `s1`

The benefit is that you won’t unnecessarily do expensive copies. The downside is that you need to be careful about the ownership of the value. Although luckily, the compiler will help you out with this. If you want to copy the value, you need to explicitly use the clone() method.

Syntax for Pointers and References

In C++, you have the concepts of pointers and references.

// This is how you get a pointer:

int* p = &a;

// This is how you dereference a pointer:

int a_copy = *p;

The & in &a and * in *p are operators. The int* is a pointer type. You announce it on both ends.

// This is how you assign by reference:

int& r = a;

// This is how you use a reference:

int a_copy = r;

The reference r is functionally no different from the original a. In C++, references are not a first-class type like in Rust, but a mechanism for passing as function arguments, or assigning to variables. You don’t need operators to get a reference, but just make the reference notation on the receiver variable side (int&). There is more nuance between lvalue and rvalue references that goes beyond the scope of this short post.

Whereas in Rust, references look like the below.

// This is how you get a reference:

let r: &i32 = &a;

// This is how you dereference a reference:

let a_copy: i32 = *r;

The & in &a and * in *r are operators. This feels like pointers in C++. However, the &i32 is a first-class reference type in its type system, a rather unique choice among common programming languages. There are a lot more rules on auto-dereferencing that go beyond the superficial resemblance.

Pattern Matching

I like the powerful Enums and pattern matching in Rust. It’s very neat.

enum Color {

Red(u8), // u8 is the type of the value, indicating the intensity

Green(u8),

Blue(u8),

}

let c = Color::Red(255);

match c {

Color::Red(v) => println!("red {}", v),

Color::Green(v) => println!("green {}", v),

Color::Blue(v) => println!("blue {}", v),

}

Borrowing (and Borrow Checker)

This is the most important/novel concept in Rust, but I would just redirect you to read the book. It gets more intuitive as you see it everywhere, and its occurrences logically make sense. Notably, in C++, you don’t have variations of self in the context of an object’s methods, but in Rust, you do because &self/&mut self are explicitly invoked in the method signatures and follow the same rules.

Conclusion

That’s it so far. There might be incorrect wordings, as these are big languages, and I try to write this article as a learner, not an expert. It is a big topic to weigh the pros and cons, comparing languages people love and care about. If you open Stack Overflow or Reddit, you will find heated discussions and debates.

I will continue with the book and write as I learn more. Hope this article helps you in your journey.